Sharing Access to Offshore Energy Within China's "Nine-Dash Line"

[By Suryaputra Wijaksana]

Last month, the Indonesian government approved natural gas exploration in the Tuna gas bloc, part of the largest untapped natural gas deposit in the world. The development of the bloc could not have come at a better time, with global energy supply increasingly under threat due to intensifying great power competition and a tightening monetary regime. Until now, energy security problems have been artificially ameliorated by a warmer winter in Europe and the looming global recession.

The exploration project should bring significant benefits for Indonesia. The government is set to receive an estimated gross revenue of $1.2 billion cumulatively until 2035 and the project would also significantly increase natural gas exports to Vietnam and cement Indonesia’s position as a major gas producer. However, it is not going to be cheap. The investment and operating costs are estimated at $1.0 billion and $2.0 billion respectively.

The location of the project is also highly contentious. The Tuna bloc lies near Indonesia’s Natuna Islands, within Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). However, geographically it is closer to Vietnam than it is to the rest of Indonesia. Harbour Energy, the company commissioned to work on the project, is also planning to build a pipeline that would export most of the gas to Vietnam.

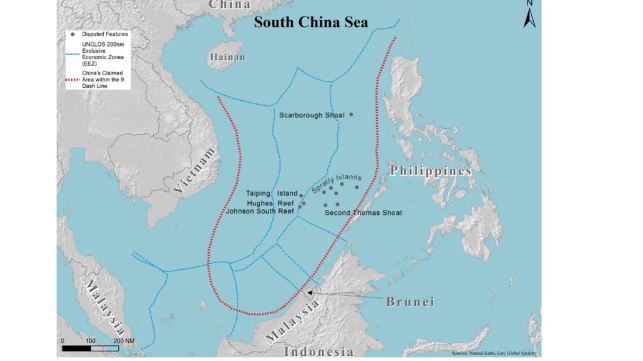

More importantly, the Tuna bloc sits squarely within the notorious Chinese-claimed “nine-dash line”, fuelling fears that China may try to intervene in Indonesia’s extraction of natural gas. So far, China’s response to exploration in the Tuna bloc has been modest. It lodged an official protest with the foreign ministry, which was met with a cold shoulder. On the ground, China has employed an aggressive show of force, sending civilian and coast guard ships to the exploration areas with the intention of intimidation. The Indonesian Navy has responded by sending some of its own ships.

China has deployed the same tactic towards other Southeast Asian claimants in the South China Sea. In September to October last year, China sent a fleet of support vessels and a militia ship to impede oil exploration in Malaysia’s EEZ. In June, Chinese Coast Guard and maritime militia vessels prevented Philippine troops from reaching their garrison in the Philippine-occupied Thomas Shoal.

From China’s point of view, it has good reasons to aggressively maintain its claims in the South China Sea. The “middle kingdom” is particularly vulnerable to shocks in the global energy markets. It imports a significant portion of its energy, and its domestic sources are either not economically viable or production costs are stifled by the dominance of state-owned enterprises.

For the moment, China has access to cheap Russian oil, but this is not guaranteed. In the short term, it gives leverage to significant buyers of Russian oil and greater bargaining power to push for lower oil prices. However, it also highlights the West’s strong grip on global financial and oil markets as Chinese shipping and insurance companies have so far proven reluctant to carry and insure Russian oil.

Despite decades-long success in increasing pressure on other claimant states in the South China Sea, recent developments seem to have turned the tide against China. Claimant states are beefing up their defences. Vietnam greatly expanded its island reclamation in 2022, creating nearly 420 acres of new land. Chinese aggression has pushed the Philippines and Vietnam – China’s old adversary – closer to the United States. And China’s actions have sparked increased defence spending across the region in the past few years.

The recent conclusion of maritime delimitations between Vietnam and Indonesia has cleared up their respective EEZs, possibly forging a path for other ASEAN member states to unite in Code of Conduct negotiations.

There are also domestic pressures brewing within China. The ongoing property crunch and demographic aging have significantly weakened domestic growth, leading to greater Chinese dependency on global markets. Adding to this is the growing risk of confrontation with the United States, coupled with looming global economic and possible financial crises.

There are signs of a softening Chinese stance in global diplomacy. The recent shift in personnel from “wolf warrior” foreign minister Wang Yi and spokesperson Zhao Lijian to the more US-friendly Qin Gang and Wang Wenbin could signal China is ready to negotiate more favourable terms with claimant states.

Indonesia and other claimant states should use this opportunity to their advantage. They should set measurable goals, such as reducing incursions by Chinese vessels into their respective EEZs, and then focus all tools on achieving those goals. They should also aim to increase the transparency of deals between member states and China, including the Belt and Road Initiative projects, where China has significant leverage.

Another possible move to increase legitimacy and access natural resource deposits would be to invite Chinese oil and gas companies or other foreign companies to operate in the disputed seas with claimant states still holding majority ownership. China could then build a network of pipelines and infrastructure connecting new explorations to its industrial cities, ensuring its supply of energy but also ensuring buyers from claimant states. Although it may take some time to implement, sharing the resources of the seas is better than the alternative in the midst of a worsening energy crisis.

Suryaputra Wijaksana is an economist at a leading Indonesian bank, specialising in macroeconomics and financial markets. He holds a master of public policy degree from the Lee Kuan Yew School, National University of Singapore.

This article appears courtesy of The Lowy Interpreter and may be found in its original form here.

Top Image: China's nine-dash line (Keanehm / CC BY SA 4.0)

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.