Forrest Rednour and the Rescue of the WWII Transport Dorchester

. . . his courageous disregard for his own personal safety in a situation of grave peril was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. - Navy & Marine Corps Medal citation, Ship’s Cook 2nd Class Forrest O. Rednour

Forrest Oren Rednour was born May 13, 1923, in Cutler, Illinois. He enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard June 19, 1941, in Chicago and received an assignment aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Escanaba as a third class ship’s cook, Nov. 1, 1941. He was subsequently promoted to second class petty officer July 6, 1942.

The Escanaba was his first cutter and it would be his last. At the time of Rednour’s assignment, this heroic cutter served in the Greenland Patrol escorting convoys between Canada and Greenland.

With heavy seas and icy water, the North Atlantic seems an impossible place to save lives. Nevertheless, the challenge of rescuing as many men as possible motivated the Escanaba’s crew to develop a system of tethered rescue swimmers equipped with parachute harnesses and leash lines, as well as rubber dry suits that insulated the swimmers from the cold water. Three of the cutter’s crew volunteered for the hazardous duty of serving as rescue swimmers, including Rednour.

Escanaba in camouflage paint scheme during its deployment with the Greenland Patrol. (Courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard)

Escanaba in camouflage paint scheme during its deployment with the Greenland Patrol. (Courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard)

Rednour and his fellow rescue swimmers drilled frequently, so they and their supporting deck crews could work in heavy seas and blackout conditions. In early February 1943, Rednour and the others had a chance to put their skills to the test. At the time, the Escanaba served as an escort for the three-ship convoy, SG-19, bound from St. Johns, Newfoundland, to southwest Greenland. Weather conditions during the convoy’s first few days proved horrendous, as they usually did in the North Atlantic winter. The average air temperature measured well below freezing, the seas were heavy and the wind-driven spray formed layers of ice on the Escanaba’s decks and superstructure.

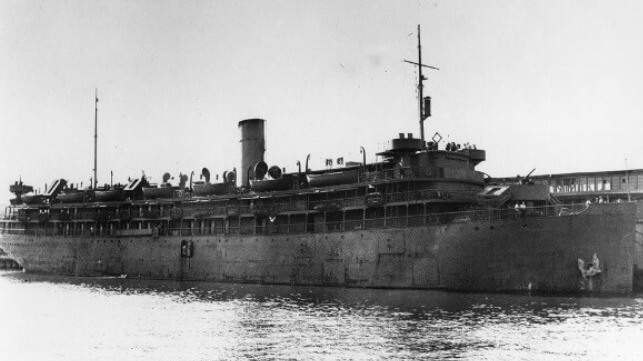

U.S. Army Transport Dorchester before its ill-fated voyage to Greenland. (Courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard)

At 1:00 a.m., Feb. 3, the enemy submarine U-223 torpedoed convoy vessel U.S. Army Transport Dorchester, which carried over 900 troops, civilian contractors and crew. Within 20 minutes, the transport slipped beneath the waves, sending surviving passengers and crew into lifeboats or the icy water. By the time the Escanaba arrived on scene, the wind was light and the seas had been smoothed by a heavy oil slick left by the lost ship. The Dorchester’s life preservers were equipped with blinking red lights to help rescuers locate floating victims at night. These red lights twinkled in the distant darkness.

During the war, the service required cutters to observe blackout conditions in nighttime operations. Hence, the Escanaba’s crew began preparations to deploy the rescue swimmers in advance, to minimize confusion in the dark. As the Escanaba steamed to the location of the Dorchester’s sinking, the rescue swimmers donned their exposure suits. Meanwhile, deck-crew members made lines ready for hauling aboard helpless survivors, secured sea ladders and dropped a cargo net over the cutter’s side.

Once on scene, the Escanaba located its first group of floating survivors, stopped and drifted toward them. Some of the men were clinging to doughnut rafts, while others remained afloat using life preservers. The victims suffered from severe shock and hypothermia and could not climb the sea ladders or the cargo net. In fact, they were incapable of grasping a line to haul them aboard the cutter. Clad in his dry suit and secured to the Escanaba by a line, Rednour swam out to the floating victims and life rafts. He checked for signs of life and secured the victims to a line so the deck crews could pull the survivors up to the cutter. Even though many victims appeared frozen to death, 38 out of 50 that appeared dead were frozen but still alive. Rednour got the floating victims to the cutter immediately, saving time and more lives.

Painting of Escanaba’s rescue operations by an unknown artist. (Courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard)

Painting of Escanaba’s rescue operations by an unknown artist. (Courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard)

Selflessly, Rednour remained in the icy water nearly four hours. Pulling rafts in close to the cutter and securing them with lines from the Escanaba, the ship’s cook was often in danger of being crushed between life rafts and the cutter’s side. He kept helpless survivors afloat until they could be secured with a line and hauled aboard the cutter. He also swam under the fantail of the maneuvering cutter to keep floating victims away from the suction of the Escanaba’s propeller. All the while, he disregarded the danger to himself as he tried to save as many lives as possible.

After eight hours of rescue operations, Rednour and the Escanaba’s other tethered rescue swimmers had saved 133 lives. However, the glow of success proved short-lived. In June, the Escanaba joined cutters Storis and Raritan to escort a convoy bound back from Greenland to Newfoundland. At 5:00 a.m., on Sunday, June 13, the Escanaba fell victim to a catastrophic explosion, believed by many to have been the result of a torpedo. The cutter sank in minutes, taking Rednour and 100 of his shipmates down with it. Only two Coast Guardsmen managed to survive the explosion and sinking.

For his heroic service, Rednour became the namesake of a U.S. Navy high-speed transport (APD-102). The only other enlisted Coast Guardsman so honored by the Navy was Medal of Honor recipient Douglas Munro. Rednour also received the Navy & Marine Corps Medal and posthumously received a Purple Heart Medal.

Color photograph of the Fast Response Cutter Forrest Rednour underway. (Courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard)

William Thiesen is the U.S. Coast Guard Atlantic Area historian. This article appears courtesy of The Long Blue Line and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.