Capacity Building Must be a Focus as Sea Piracy Expands

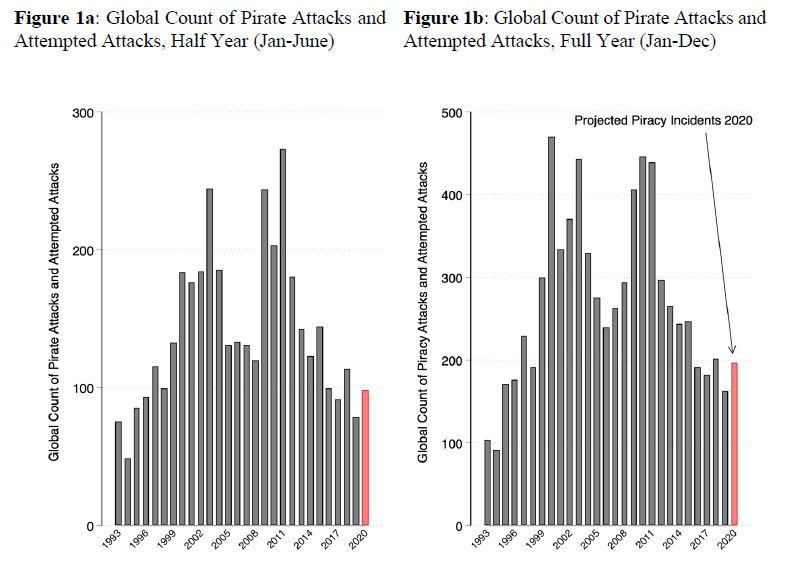

ReCAAP published its half-yearly report in July warning of a dangerous increase in pirate attacks in Asia. The organization reported 51 total incidents from January through June. This represents an 82 percent increase in sea-pirate attacks from the first half of 2019. The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) recorded a similar surge in piracy incidents. Attacks doubled in the first half of 2020 compared to 2019 (see Figure 1). The escalation in pirate activity is not confined only to Asia. Both West Africa and the Americas have witnessed increases in sea-piracy over the past two years as well. Globally, we’re on a path to see a 20 percent increase in piracy in 2020 compared to 2019.

To be sure, pirate attacks remain well below their most recent high in 2010. In that year, not only were Somali pirates responsible for more than 200 attacks and attempted attacks against ships in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Indian Ocean, but these same Somali raiders also hijacked at least 49 vessels. In 2019, the IMB reported only four ship hijackings, none of which occurred off the Somali coast. So far in 2020, the IMB reports only one hijacking; a fishing boat seized in the waters of the Ivory Coast. Despite successes with Somali pirates and an overall decrease in vessel hijackings, recent trends in commerce raiding warrant concern.

Singapore Straits

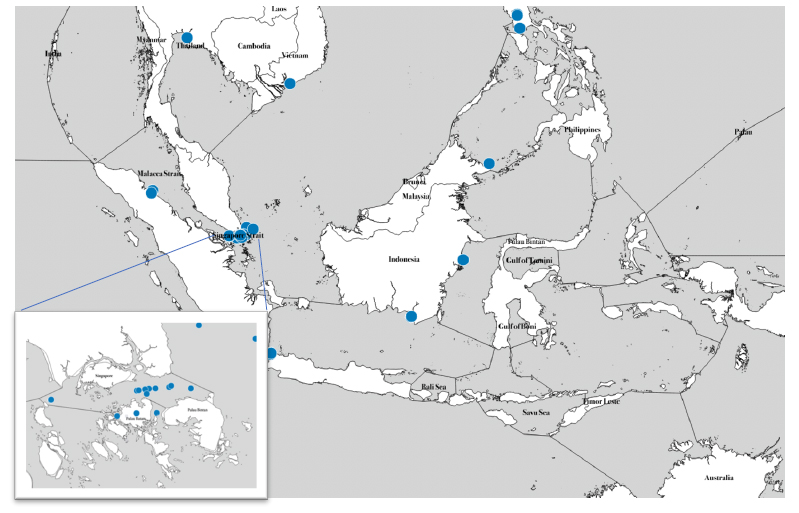

Piracy in and around the Singapore Straits has visibly increased over the past several years and is at its highest level since 2015. Of the 35 pirate attacks that occurred in Southeast Asia from January through June of 2020, fourteen happened in the Singapore Straits or nearby at anchorages on Pulau Batam. Pirates attacked another two ships proximate to the Singapore Straits in the Natuna Sea and three other ship robberies occurred at Belawan Port on Sumatra (see Figure 2). Most of the ships boarded in the Singapore Straits were steaming at the time of the attack and all but one was a large product tanker or cargo carrier. Currently, the piracy we see in Southeast Asia generally, and the Singapore Straits more specifically, remains mostly opportunistic rather than organized. Only a few years ago Indonesia and Malaysia formed a rapid reaction force to combat a surge in sea-piracy in the Malacca and Singapore Straits. Attacks dropped significantly soon after, going from over 60 incidents in 2015 to fewer than 10 in 2016. Exiting the Singapore Straits near Little Karimun Island was particularly dangerous in 2014 and 2015. The recent rise in sea-piracy in and around the Singapore Straits is attributed by some to complacency in enforcement.

Figure 2: Map of Southeast Asia and the Singapore Straits (inset) showing the Locations of Pirate Attacks, January 1 – June 30, 2020

Sulu and Celebes Seas

Pirate attacks in the southern Philippines have recently received considerable attention as Abu Sayyaf, an Islamic separatist group, took advantage of ship traffic across the Sulu and Celebes Seas to fund-raise through maritime kidnappings. In response, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines established coordinated counter-piracy naval patrols that helped check Abu Sayyaf’s activities. The US Navy also stepped up its own patrols, increased information sharing with local maritime security forces, and participated in training exercises all designed to counter illicit activity and protect maritime commerce. Still, ReCAAP once again issued a warning about possible crew abductions by the Abu Sayyaf group in May of this year and there is some concern that ship attacks may increase as Filipino security forces continue their assault on the group. A key leader of Abu Sayyaf was recently captured by local police in Davao City and reprisals are anticipated. The August 24th bombings in Jolo, only 9 days after the arrest, are believed to have been carried out by Abu Sayyaf militants.

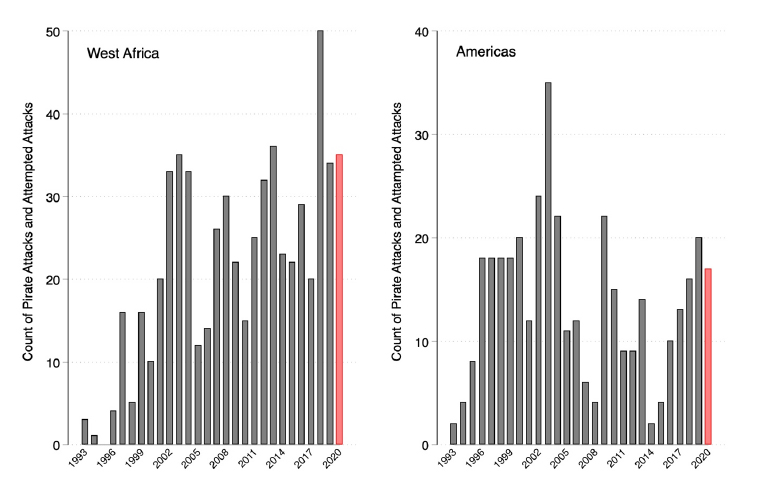

West Africa and the Americas

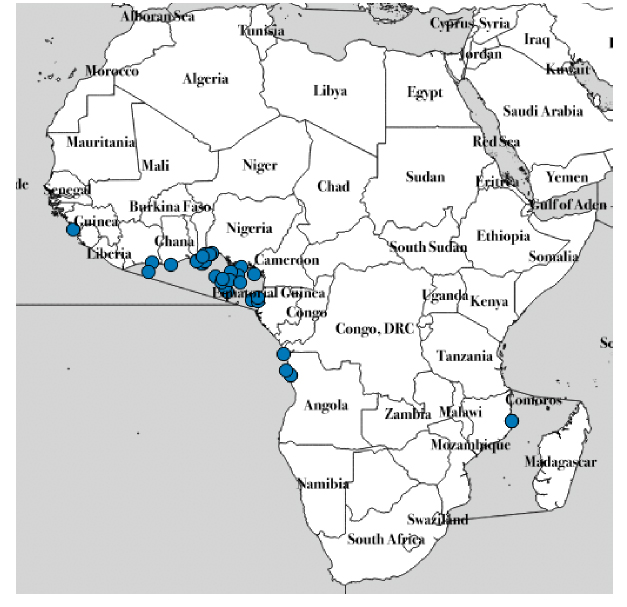

In both the Gulf of Guinea and Latin America pirate attacks have been on the rise, driven by poverty, joblessness, violence, and corruption (see Figure 3). The incidents off West Africa have also been increasingly violent. Armed with assault rifles, shotguns, and knives, the pirates in the Gulf of Guinea kidnapped 49 crewmembers in the first half of 2020, which represents a 50 percent increase from 2019. Recently, in fact, two Russian sailors were kidnapped from a refrigerated cargo ship off Lagos. This is just one of at least 10 incidents in 2020 involving the abduction of crew members and it continues a trend of seafarer kidnappings conspicuous in the Gulf of Guinea. Over 90 percent of crew kidnappings today occur in the waters off of West Africa and the Joint War Committee of Lloyd’s of London continues to list the EEZs of Togo, Benin, and Nigeria as areas of enhanced risk.

Figure 3: Maritime Piracy and Armed Robbery on Ships in West Africa and the Americas (January-June 2020)

Pirate attacks against oil platforms and supply vessels in the Bay of Campeche also appear to be increasing. The US government issued a security alert in June of this year warning Americans traveling by boat in the southern Gulf of Mexico to be extra cautious. Armed criminal groups look especially active between the cities of Veracruz and Campeche. Hundreds of oil facilities dot the bay and supply boats constantly shuttle work crews and provisions to and from the Mexican coast. Although the International Maritime Bureau reports only 4 pirate incidents in the Bay of Campeche in the first half of 2020, the US Office of Naval Intelligence reports twice that number and others think attacks are much higher than that.

Figure 4: Map of Africa showing the Location of Maritime Pirate Attacks (January-June 2020)

Local Capacity Key to Reducing Maritime Crime

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Criminal actors exploit spaces that lack effective law enforcement and use proximate trade routes to steal cargo and abduct crew members from passing ships. While governments in Southeast Asia and West Africa are enhancing and modernizing their maritime capabilities, most large naval power projection remains an unsuitable and mostly ineffective policy tool for combating illegal maritime activities. Maritime law enforcement capacity, improved regional cooperation, and better local governance can more efficiently target criminal actors and reduce community incentives to engage in maritime crime. The U.S. helps strengthen the capacity of Southeast Asian partners, such as the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Indonesia, by providing surveillance equipment, patrol craft, helicopter upgrades, and drones. Through the Obangame Express, a multinational naval exercise, the U.S. also helps build law enforcement capacity in the Greater Gulf of Guinea focused on maritime domain awareness. France, the U.K. and China have similarly provided ships, equipment, and training to West African governments to help reduce sea-piracy and other maritime crime.

The COVID pandemic has exacerbated conditions that drive sea-piracy, such as poverty and joblessness. The WTO expects global trade to drop between 13 and 34 percent in 2020 and the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank in Washington DC, anticipates sizable drops in the GDP of many piracy-prone countries, such as Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Mexico. Further, ships will likely become easier targets. Less consumer spending means less trade, which means less revenue for shipping companies to spend on armed guards or other modes of ship protection. Vessel crews are already stretched thin on merchant ships and COVID has only reduced available manpower. On a positive note, both ReCAAP and the International Maritime Bureau report fewer pirate attacks and ship robberies in July and August compared to the same months in 2019. Perhaps the surge in sea-piracy observed during the first half of this year led governments to re-focus and intensify their counter-piracy efforts. Or, possibly we are simply witnessing a short lull in the storm.

About the author: Brandon Prins is Professor of Political Science and Global Security Fellow with the Howard Baker Center for Public Policy at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville. Funding for this project was originally provided by the US Department of Defense, Office of Naval Research, through the Minerva Initiative.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.