The Future Shipping Company: Autonomous Shipping Fleet Operators

You may have heard of tech industry buzz words like software-as-a-service (SaaS) or car-as-a-service (CaaS). In the SaaS scheme, the user does not need to install and sacrifice a portion of storage for software. Instead, software can be operated through a cloud connection and with much higher computing capacity. Difficult calculations and simulations can be run on very high capacity computers in a cloud space. CaaS is a more technical version of the term “uberization.” Instead of having your own car, other car owners provide you with mobility, much like hailing a taxi but at much lower cost and with more convenience.

The idea of the as-a-service concept has a long history in the shipping business. I call it Ship-as-a-service (SHIP-as-a-service). Traditional time charters are a typical example of SHIPaaS. With the rise of independent ship owners, many big exporters and importers charter a fleet of ships dedicated to their cargo movements. Today you can even find non-asset ship operators which simply time charter-in a number of ships and spot charter-out for end customers. It is also an investment question whether to own or charter ships. During the industry’s corporatization period, many shipping firms have evolved into SHIPaaS providers, even though we do not use this terminology.

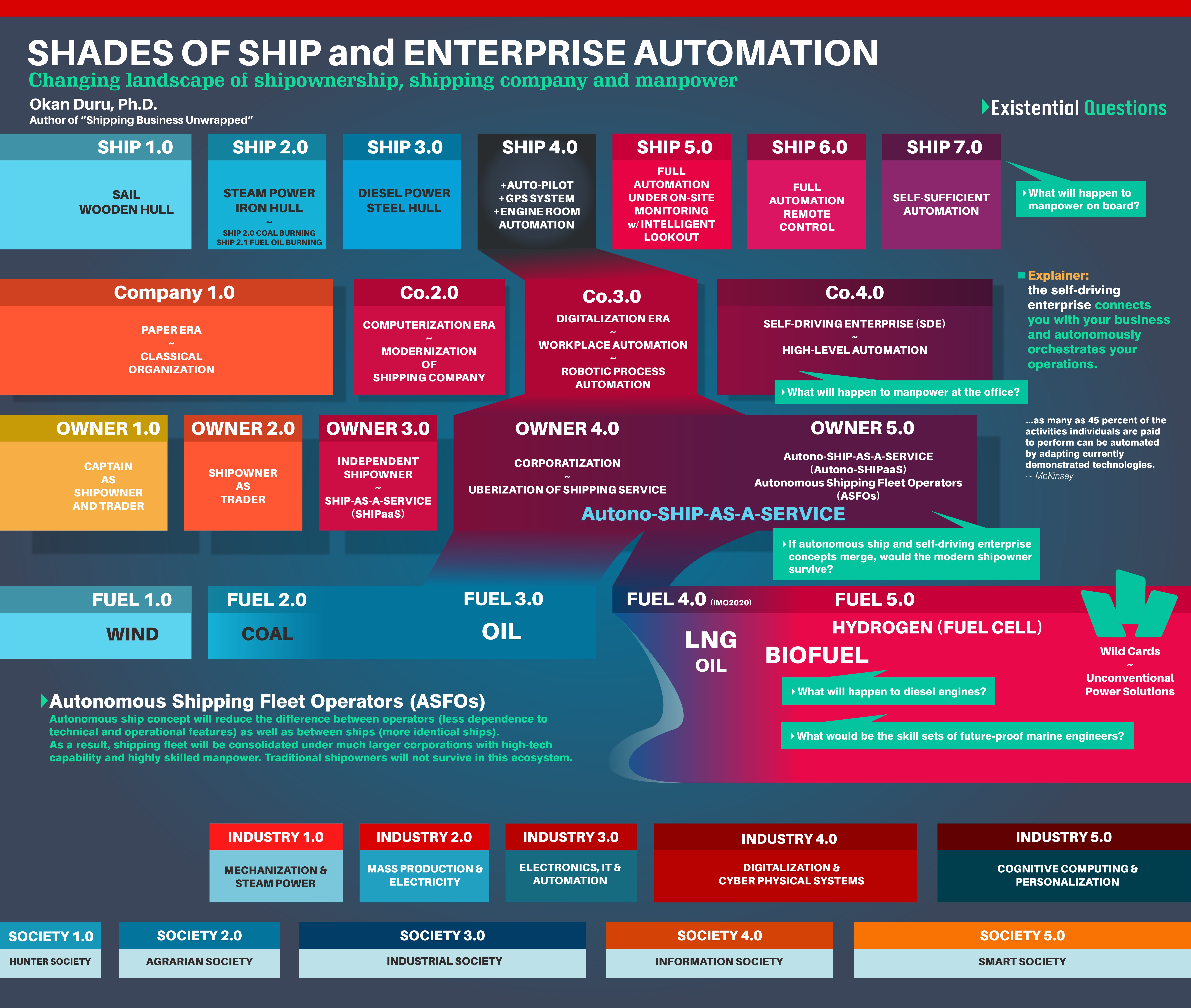

On the other hand, automation is transforming so many things. Vehicles are automated and office work is also increasingly automated. So we have two facets of the automation in general: In the shipping industry, autonomous ships will transform the ship itself while workplace automation transforms the shipping company. In the infographic above, I label the evolution of the ship as SHIP x.0 beginning from the 1700s through roughly 2050s. Considering major changes like the use of iron and steel or steam and diesel power, SHIP 4.0 represents the current technology. From SHIP 4.0 to 7.0, I perceive three major transformations: 1) Implementation of hybrid navigational and engine room automation with on-site monitoring, 2) shifting the majority of seafarers to off-site monitoring and governance (i.e. remote control) and 3) self-sufficient automation which does not need human intervention in any operations. As a side note, technology for the above-mentioned developments is almost there. We just experience these changes with the institutional adaptation and economy of implementation, not due to the lack of technology.

In the business consulting space, one of the leading concepts is the self-driving enterprise or workplace automation. By extensive use of technologies such as robotic process automation and by transforming commercial operations, the need for office space will probably decline dramatically. According to some recent reports by various consulting firms, more than 30 percent of existing office work can be automated by currently available technologies. A much higher level of automation means getting much closer to the self-driving enterprise in which most office work is shifted to intelligent systems and “bots.” Then, key decision makers will focus on things that are difficult to automate. As I recently introduced in an industry event, the algorithmic trading concept can also be implemented in investment management. So, even some financial decisions may be automated too.

Autono-SHIPaaS and Neo-Shipowner

By investigating such developments separately and isolated from other disruptions, we may expect things happening as illustrated above. However, when you combine many of these ideas and disruptions of other kinds (e.g. automation in shipbuilding, new power technologies), the big picture changes slightly. One major component in this equation is the Autonomous SHIPaaS (Autono-SHIPaaS). Autono-SHIPaaS changes the profile of traditional shipowner. The need for technical manpower on board and at the firm declines as the company transforms. The shipowning entity turns into a technology-led organization with more focus on maintaining computational capacity. You may consider the analogy of Tesla, which is going to be a major car manufacturer soon and is already the top seller for the luxury sedan segment in the United States. Traditional car makers with century-old experience could not deal with the disruption of Tesla. The driverless car is going to be the norm of the automotive industry - and driverless navigation is a much more difficult computational problem compared to ship navigation.

In such an ecosystem, the market boundary for newcomers may be lifted and/or requirements may change for owning and operating ships. It would not be surprising to see a Tesla of shipping industry which rapidly cannibalize the traditional market. In a recent development, Softbank and Toyota introduced their joint venture, MONET Technologies Inc., which will develop and establish the Autono-MaaS (mobility-as-a-service) for Japanese market. In this concept, users do not need to own a vehicle. Whenever they need mobility, they will be using an app similar to Uber to call a driverless vehicle which can be a personal car, a mini bus or a family size leisure vehicle.

Neo-shipowners, autonomous shipping fleet operators (ASFOs), will eventually adapt this concept into the shipping industry. ASFOs will own large fleets of autonomous ships controlled by intelligent systems and with a minimal manpower requirement. Some technology firms may fill this gap by utilizing their capacity, or some of traditional shipowners may transform to ASFOs to take advantage of being "first mover." In my classification, ASFO is the next-generation shipowning entity (Owner 5.0).

The number of major carriers in the liner shipping segment has declined significantly since the 2000s. The top five carriers control more than 50 percent of the market. Introduction of ASFO will probably accelerate this trend, and it would not be surprising to see even more consolidation. In the bulk shipping segment, it is a relatively competitive market with many carriers. In contrast to liner shipping, it would be a much more disruptive change, and newcomer ASFOs may redefine the rules of the game. New methodologies in cargo handling, port operations and shipbuilding will pave the way for ASFOs and make it easier to enter this market. For current shipowners, that may be classified as the weakness of the market, but it will be a fruitful opportunity for technology-focused newcomers. In a strategic definition, technological strength may take advantage of the opportunity in an offensive way to target the weakness of slow-steaming firms who could not manage the transformation.

One critical factor in this scenario is the way of powering ships. Apart from the current disputes and challenges of the IMO 2020 sulfur cap, we expect much dramatic changes in the energy resources. A Finnish company, Neste, is going to build a biodiesel production unit in Singapore, and there are many more developments in the biofuel technologies. I expect that LNG and Biofuel will lead the current power propulsion systems. However, dramatic changes that I refer are other kinds of energy generation systems. For example, when MAN Energy Solutions acquired 40 percent of the shares of the electrolysis technology company H-TEC Systems, I did not see this as side-business for a leading engine maker - I saw it as a survival strategy. Currently, there are technological developments being tested in laboratories, and the cost of alternative energy resources is declining much faster than common perception. Based on my ongoing investigations, the fossil fuel era may end much quickly than traditional projections.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Considering all of these elements, the incubation period may still take a decade, but the tipping point does not seem so distant. The term disruption is so abused and exaggerated, and it has become a cliché of our time. However, a “real” disruption may hit the industry in less than two decades. It will not only change material and manpower, but it will also change institutions, organizations and the behavior of decision makers. It would be much wiser to discomfort the comfort zone of institutions before predatory strategies arrive to do that.

Okan Duru, Ph.D. is the director of the Master of Maritime Studies program at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.