RightShip: 8,800 Seafarers Have Been Abandoned in the Last 20 Years

Imagine being on the deck of a ship, sunny skies above, the gentle lapping of waves at the hull. It might be attractive to begin with, but then imagine that day stretching into weeks, then months. Add cold, wet and windy weather. Finally, factor in a lack of food, money, internet access and nothing to do all day long, combined with a complete lack of control over when you will see family, friends or loved ones again.

In Crew Welfare Week, we’re pausing to reflect on the fact that over the last 20 years this has been the situation faced by more than 8,800 seafarers around the world, trapped on ships that are no longer sailing anywhere, or literally dumped at the nearest port and left to fend for themselves.

Some of them are anchored near harbours, some of them float way out on the ocean, but none of them can leave. The reasons for abandoned ships - and the abandonment of those seafarers on board - are many and varied. From owners running out of money for a voyage, to bankruptcy, to a ship reaching the end of its shelf-life and costing more to repair than to leave behind, to more extreme or unusual cases like mutiny or pandemic - crew abandonment is a real and frightening issue.

Officially, abandonment is when a shipowner fails to cover the cost of a seafarer’s repatriation, has left seafarers without necessary maintenance and support, or when they have otherwise unilaterally severed their ties with the crew, including failing to pay contractual wages for a period of at least two months.

But each one of these abandoned seafarers is also an individual, with families and friends worried about where their loved ones are, and when they will see each other again.

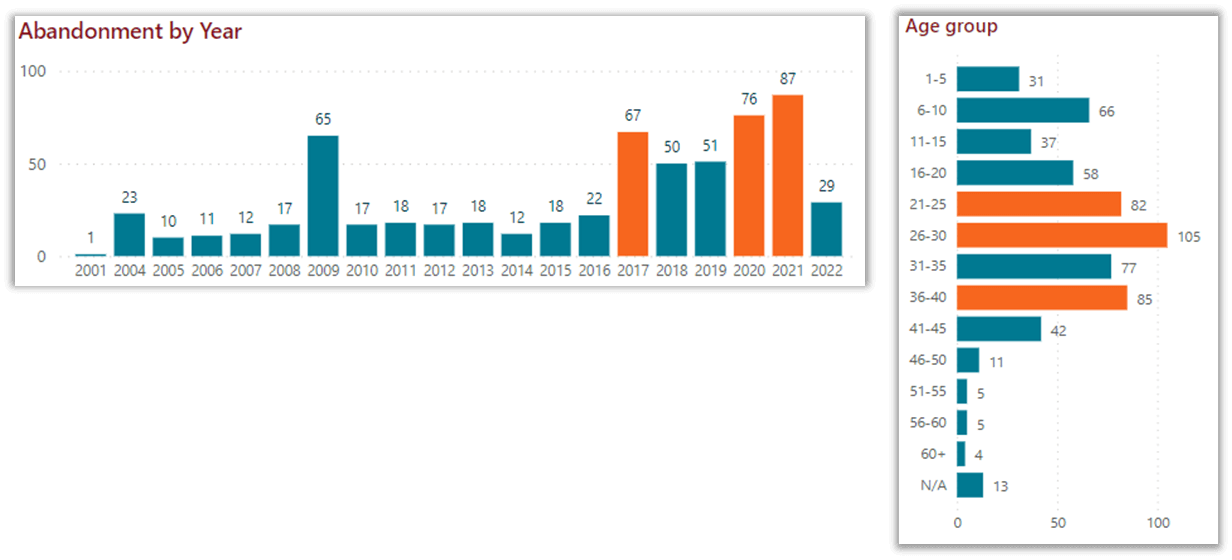

Abandonment by number of vessels per year and age group of ships

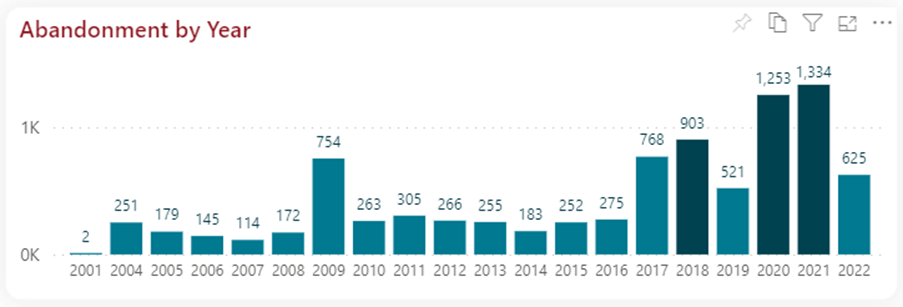

Abandonment by number of seafarers affected per year

Why does RightShip care?

Seafarers are the lifeblood of the maritime industry and the global economy, with 90% of goods in the world moved by ships. There are around 1.6 million seafarers – made up of around 770,000 officers and 870,000 ratings - and a large proportion of those seafarers are from underdeveloped or developing countries, or island states.

According to a statement from the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), “Seafarer abandonment is a serious problem that can blight the lives of those caught up in it.

It must be tackled, and it needs continual cooperation, not just between IMO and International Labour Organisation (ILO) and non-governmental organisations devoted to a seaman’s welfare, but with flag and port states and other industry groups too. We all have a human duty to protect seafarers.”

At RightShip, as an organisation focused on zero harm in the maritime industry, we want to play our part in raising awareness, highlighting and acting against the substandard and inhumane social acts that sometimes take place at sea. The data that we are collecting ultimately helps us identify those operators who have little, or no interest, in the welfare of their crew – and enables us to make others aware of their behaviour too.

We believe that change is on the horizon. We think our data will persuade those yet to be convinced that taking up the social responsibility of crew welfare is essential. In a sector facing accusations of neglect and indifference – and potential crew shortfalls running into tens of thousands – some might say that the time has come to start calling out leaders and laggards in the crew welfare stakes.

However, we know that our status as a trusted third party, and our history in managing and analysing data, gives us a strong position of impartiality. We want to act as a key stepping-stone for charterers and ship-owners across the world on a journey towards improved crew welfare. We’re hopeful that tools like our Crew Welfare Assessment - and our background research - can encourage those in the maritime industry to make moves towards ‘doing the right thing’.

The law says – insurance is necessary

On 18 January 2017, important new rules came into force on abandonment. Since this date, under the Maritime Labour Convention 2006 (MLC), shipowners need to have insurance to assist seafarers on board vessels if they are abandoned. By law, all ships whose flag states have ratified the MLC must have their insurance certificate posted in English, in a place visible to seafarers. The document should provide the name of the insurer or financial provider, and their contact details.

Regretfully, while the convention has been ratified by the equivalent of 95% of world tonnage, less than 60% of IMO’s 175 individual member states have ratified it. This, along with a lack of adequate and competent inspectorates across the world to regularly inspect against MLC requirements and take necessary action means that a two-tier system exists where seafarers can be left subject to abuse and mistreatment. Regulation is difficult to enforce at sea and policing of vessels even more so – it’s a real case of out of sight, out of reach.

At RightShip, we can’t enforce the rules either. However, we can keep track of who’s breaking them – and what’s being done about it. Back in 2017, David Hutchison, a Marine Assurance Coordinator for RightShip based out of Melbourne, began compiling statistics on abandonment, which continues to the present day.

He uses information provided by the International Labour Organisation – including the vessel name, IMO number, date of abandonment – combined with facts and figures from RightShip databases. This data includes the Document of Compliance (DoC) company, the ship’s Technical Manager, Commercial Manager, Commercial Operator, Registered Owner and Beneficial Owner.

Tracking the beneficial owners and commercial operators is a powerful step in an industry where drawing connections between the origins of a fleet and abandoned vessels can be difficult to discern.

Additionally, we started keeping tabs on those entities that were involved with, or had knowledge of, an abandonment but did not help resolve the issue. David has dedicated himself to tracking back a decade and further in some cases, investigating the causes and resolutions for lost ships and people worldwide.

Where are we now?

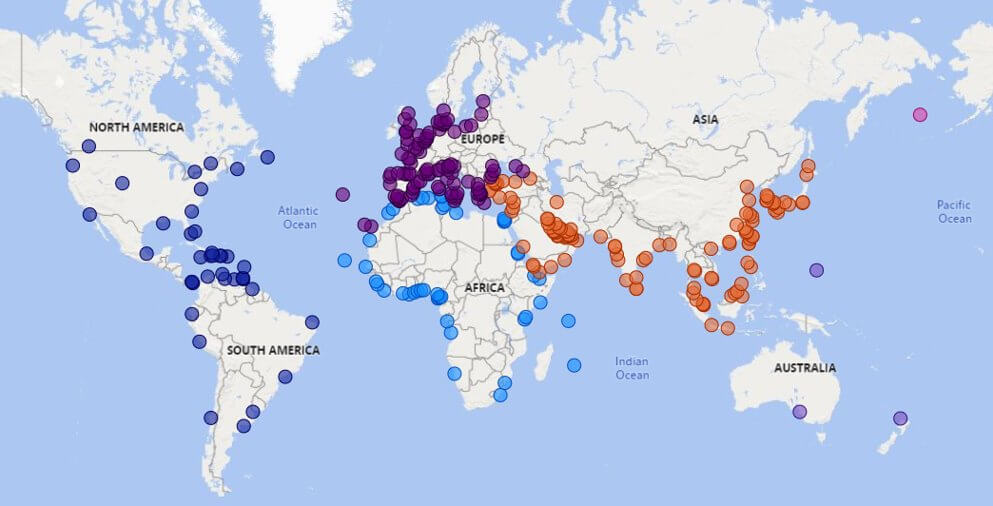

This combination of data creates a stark picture of abandonment, spreading across all continents, 104 countries and 82 flag states. And David’s most recent statistics make shocking reading. At 1 June 2022, the total number of seafarers that are or have been abandoned worldwide over the last 20 years, stood at 8,820 people, on 628 vessels.

The greatest number of people abandoned by nationality are from India, with 1,341 seafarers cut adrift, running down through 104 countries, to Armenia, Ecuador, Germany, Malaysia, the Maldives, Sa Tome and Principe, Senegal, Serbia and Montenegro and Taiwan, all with one apiece. Sadly, given the current conflict, Ukraine and the Russian Federation also both have a high number of abandonments.

The type of vessels abandoned also varies widely - with general cargo ships (33.7%), bulk carriers (9.3%) and chemical products / tankers (7.3%) featuring most highly in a list of 59 vessel descriptions. Incredibly, some of these vessels are abandoned twice. Others cannot be identified even though we know they exist, as no IMO number has been listed.

The most common age for an abandoned vessel is between 26 and 30 years, with 16.9% of the 628 vessels falling into this category, though, shockingly, some 32 vessels were abandoned in their first five years of sailing.

Perhaps most horrifying is the time that it can take to ‘settle’ an abandonment - when a case is satisfactorily resolved, the crew are paid their outstanding wages and repatriated to their home port. But according to David’s statistics, since 2004, there are 30 vessels where abandonments have been in dispute for more than a decade, with more than 400 seafarers still waiting for their cases to be settled. On average, crew remained onboard for seven months before being repatriated, with the longest being a 39-month-long wait to go home.

Most abandonments seem to take between five and ten years to resolve - an incredible length of time for those potentially left trapped and out of pocket, and unnoticed by most of the world.

Abandonments by location

What this means for seafarers – and what can be done?

When a ship is abandoned, seafarers do not receive the pay they are owed. If they leave the vessel, they are potentially saying goodbye to years of unpaid wages, millions of pounds that goes to support their loved ones – and in some cases their entire community.

The standoff begins, and continues, between crew and ship owner, with charities like the Mission to Seafarers supporting the crew, with food, water and other supplies. Many of those on board will face issues with their documentation being held by the ship’s management or these documents expiring while they are at sea. International law also prohibits vessels without crew, known as ‘ghost ships’, as they are a safety hazard.

The waiting takes its toll on mental and physical health, the separation from family and friends seemingly unending. Organisations like the International Seafarers Welfare and Assistance Network (ISWAN) intervene where they can, providing phone line support and emergency funding when seafarers absolutely must return home but have no means to do so.

RightShip is hopeful that sharing this data could lead to meaningful change. That we’ll see an uptick in those accessing the Code of Conduct and completing our self-assessment. We’ll encourage our charity partners to share our statistics on seafarer abandonment in the hope that the message starts to get through to owners and operators.

And as we look to the future, we will progress from ‘carrot’ – to more ‘stick’. We already identify vessels linked to a company associated with abandonment in our portal. We don’t recommend them to our customers for voyages, and we mark them as 'unacceptable' during the vetting process. Operators who have little regard for the welfare and human rights of their crew must not be allowed to continue to operate, but we know that we can do more. We hope that these stakeholders will begin to understand that if they do not improve their crew welfare, it will start to affect their bottom line, and that the opportunity to be leaders in the sector is a far more attractive prospect.

We want a maritime industry that causes zero harm – and a safe and sustainable future for all who live and work at sea. Protecting and safeguarding seafarers throughout the world is a critical element of having safe crew and safe ships, leading to safe oceans and seas.

Andrew Roberts is RightShip’s Head of EMEA.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.