New York's Climate Suit: What's the Measure?

by Dr. Gavin Law and Amy Bowe

On January 10, 2018, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a lawsuit against ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, BP and ConocoPhillips, claiming the companies intentionally misled the public about the effects of climate change in order to protect their profits. At the same time, de Blasio indicated that he and comptroller Scott Stringer would submit a joint resolution instructing the city's five pension funds to begin exploring ways to divest their fossil fuel holdings. Between them, the funds hold $5 billion worth of securities in over 190 fossil fuel-related companies.

The lawsuit seeks damages to cover costs incurred by the city to adapt to the effects of climate change, both those already observed and anticipated future effects. New York has reportedly appropriated $20 billion towards infrastructure upgrades, education campaigns and public health programs intended to protect the city against rising seas, hazardous weather and extreme heat.

San Francisco and Oakland filed similar lawsuits against the same five companies in September 2017, asking state courts to require the companies to fund infrastructure the cities say is necessary because of climate change.

Assessing blame

The lawsuit targets ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, BP and ConocoPhillips, on the basis that they are the top five investor-owned companies “measured by their contributions to global warmings.” Mayor de Blasio provided no details on how the city is measuring the companies' contributions to global warming. However, his statement, "We are going after those who have profited" would seem to indicate that the city is trying to hold the companies accountable for emissions resulting from the combustion of the oil, gas and refined products they produce, as well as their own direct emissions from operations. ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron and BP are all integrated companies that produce and sell refined products, as well as oil and gas, and ConocoPhillips did have downstream operations until it spun-off its refining and retail business in 2012.

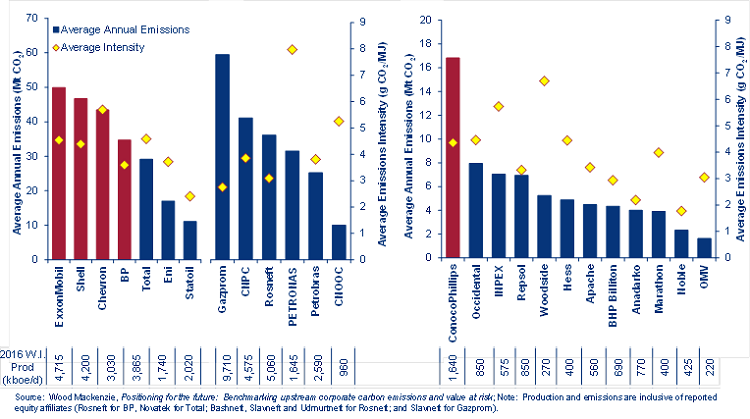

Wood Mackenzie's own analysis of the companies' upstream oil and gas emissions, as part of our recently completed multi-client study, Positioning for the future: benchmarking upstream corporate carbon emissions and value at risk, provides a more nuanced perspective. Measured on the basis of absolute emissions, direct and indirect, ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron and BP do rank as the largest emitters amongst fully publically owned oil and gas companies.

However, Gazprom, which is a joint-stock company with just shy of 50 percent public ownership, is forecast to have emissions 20 percent higher on average over 2016-2025 than ExxonMobil, the largest of the majors, reflecting the fact that its upstream production portfolio is twice the size of ExxonMobil's. Moreover, ConocoPhillips' absolute emissions from its upstream operations rank below those of Total and Eni, which are both publicly owned.

Wood Mackenzie's data excludes emissions from downstream operations, as well as from combustion of the gas and refined products sold. However, as some of the largest, publically-owned downstream and midstream operators, one would expect absolute emissions from the companies' integrated businesses and product sales to also rank amongst the largest in the world. Again, ConocoPhillips is an exception, having exited the refining business six years ago.

2016-2025 average annual emissions and emissions intensity

In terms of gauging companies' emissions performance, however, absolute emissions are perhaps not the best indicator. Instead, emissions intensity, which measures the amount of emissions released per barrel of oil and gas produced, controls for differences in size and provides a better benchmark by which to compare companies.

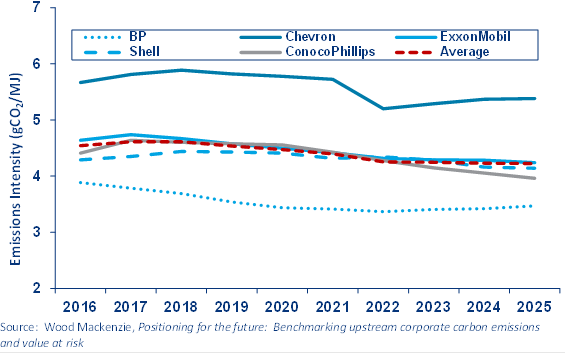

On this basis, many of the publicly owned large market capitalization companies have higher or equal emissions intensities to the majors targeted. Moreover, Wood Mackenzie's projections suggest that the emissions intensities of all five companies' upstream portfolios will fall over the next seven years, as they address flaring, implement a variety of other mitigation measures and shift out of emissions-intensive resource themes, such as oil sands. Of the five companies targeted, Shell and ConocoPhillips have already sold out of Canadian oil sands, and Total announced its intentions to exit the sector when market conditions allow.

Forecast evolution of upstream emissions intensity: 2016-2025

Burden of proof

New York City will need to provide compelling evidence as to why ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, BP and ConocoPhillips alone should be held accountable for damages. Though they do represent some of the oil and gas industry's largest emitters in absolute terms, other companies, both within the oil and gas industry as well as in other, emissions-intensive industries, such as power generation and mining, with at least partial public shareholdings have larger or equivalent emissions footprints.

Similarly, the companies rank comparably or better than other publicly owned oil and gas companies on the basis of emissions intensity, which is a more standardized metric by which to measure companies' emissions performance. Moreover, they are all starting to take steps to reduce the emissions intensities of their upstream portfolios.

Dr. Gavin Law is head of Gas & Power Consulting at Wood Mackenzie, and Amy Bowe is Director, Upstream Consulting at Wood Mackenzie.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.