How Organized is China's Maritime Militia?

The PRC defines its militia as “an armed mass organization composed of civilians retaining their regular jobs,” a component of China’s armed forces, and an “auxiliary and reserve force” of the PLA. Once conceived as a major component in the concept of “People’s War,” the militia in contemporary Chinese military planning is now tasked with assisting the PLA “by performing security and logistics functions in war.” The maritime militia, a separate organization from both the PLAN and China Coast Guard (CCG), consists of citizens working in the marine economy who receive training from the PLA and CCG to perform tasks including but not limited to border patrol, surveillance and reconnaissance, maritime transportation, search and rescue, and auxiliary tasks in support of naval operations in wartime.

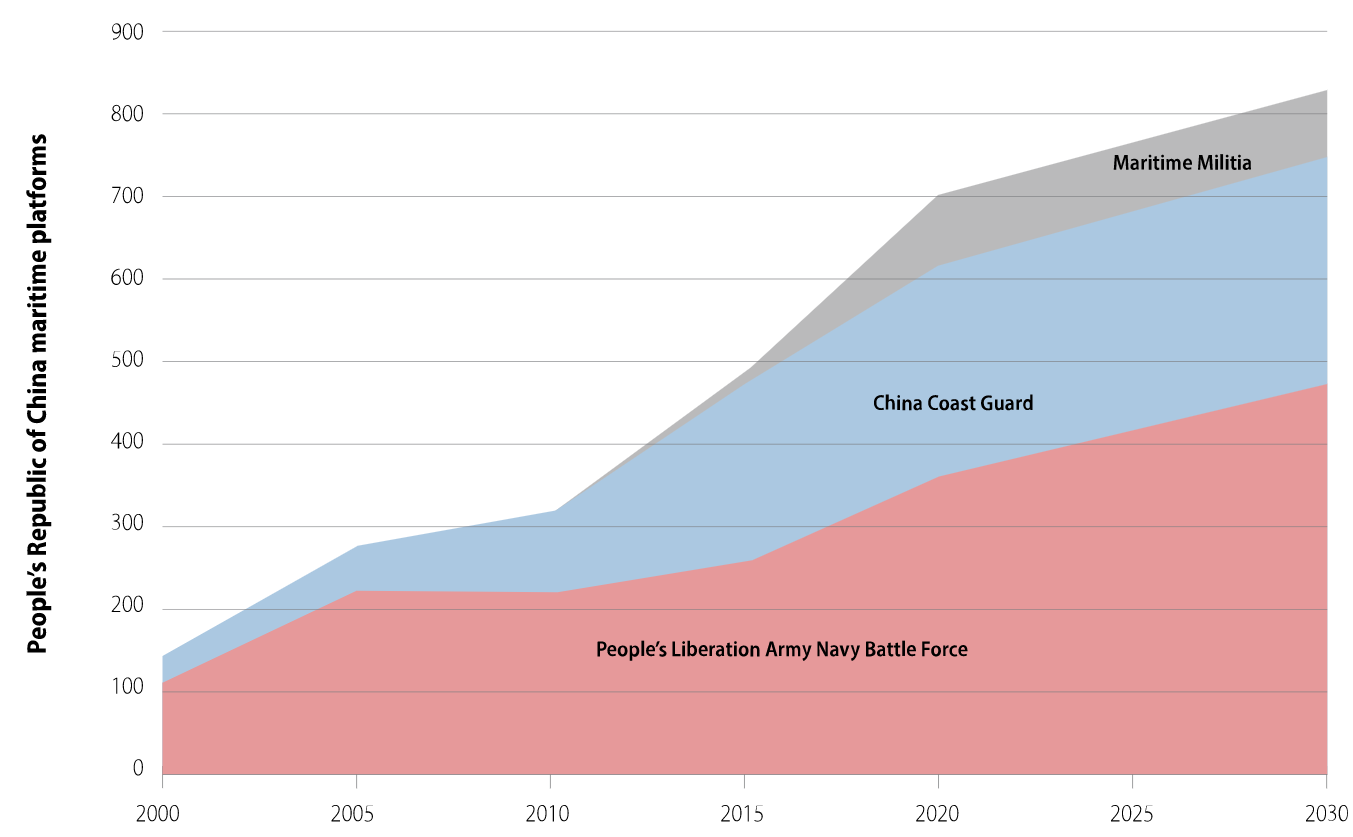

Growth of China’s Maritime Forces (From "Advantage at Sea: Prevailing with Integrated All-Domain Naval Power," December 2020, USCG/USN/USMC)

The National Defense Mobilization Commission (NDMC) system, comprised of a national-level NDMC overseen jointly by the Chinese State Council and the PLA’s Central Military Commission and local NDMCs at provincial, municipal, and county levels with a similar dual civilian-military command structure at each level, has traditionally been tasked to manage administration and mobilization of the militia. Following the PLA’s 2016 reorganization, a National Defense Mobilization Department (NDMD) has been established under the Central Military Commission to oversee the provincial-level military districts and take charge of the PLA’s territorial administrative responsibilities, including mobilization work.

The head of the NDMD is appointed as the secretary general of the national NDMC, in which China’s premier and defense minister serve as the director and deputy director, respectively. In addition to the NDMC line, the State Commission of Border and Coastal Defense system—also subject to a dual civilian-military leadership—has its own command structures running from the national to local levels, and it shares responsibility for militia administration, mobilization, and border defense. There is a significant crossover between the lines of authority.

The militia has played a major role in asserting Chinese maritime claims in the South China Sea. This includes high-profile coercive incidents such as the 2009 harassment of USNS Impeccable, the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff, and the 2014 HD-981 clash. Xi’s 2013 trip to Hainan—the island province with administrative authority over the South China Sea that has organized local fishing fleets into active maritime militia units—unleashed a nationwide push to build the militia into a genuine third arm of China’s “PLA-law enforcement-militia joint defense” maritime sovereignty defense strategy. Since it is comprised of both civilians and soldiers, according to the Chinese rationale, the militia can be deployed to strengthen control of China’s “maritime territory” while avoiding the political and diplomatic ramifications that might otherwise be associated with military involvement.

The surge of propaganda notwithstanding, several issues confront Beijing before the maritime militia can effectively function as the third arm in collaboration with the PLAN and CCG. First, the wide dispersion of the maritime militia at sea makes it harder to control than land-based forces. Second, it is unclear through what institutionalized cross-system integrator(s) maritime militia forces coordinate with the CCG or with the PLA’s theater command system that operates active-duty forces. PLA commanders and officers have openly discussed the problems of who commands the militia forces, under what circumstances, and with what authorization; who is authorized to review and approve the maritime militia’s participation in what types of maritime rights protection operations; and who is responsible for militia expenditures. Due to these uncertainties, some PLA commanders have urged further standardizing the maritime militia’s command, control, and collaboration structure.

Budgetary shortfalls complicate the training, administration, deployment, and control of the maritime militia. As of 2010, only about 2 to 3 percent of China’s national defense budget was used to fund militia training and equipment, with additional funding coming from local governments. Local funding has proven inadequate to compensate for gaps in central government outlays. A guideline issued by Hainan in 2014 stated that the provincial and county/city/prefecture governments each would be responsible for 50 percent of the province’s maritime militia expenditure. For that year, the provincial government earmarked 28 million renminbi (RMB, or Chinese yuan) for the maritime militia, a minuscule quantity given the huge costs of recruitment, administration, training, and deployment (1 RMB is equal to about 0.15 USD). According to a 2014 estimate, one week of training for a fifty-ton fishing boat costs over 100,000 RMB for crew lodging and compensation for lost income. To spread out the financial burden, common practice now holds that “whoever uses the militia pays the bill.”

Even so, funding remains a key hurdle. In 2017, the commander of the Ningbo Military Subdistrict (MSD) under the Zhejiang Province Military Subdistrict complained in the PLA’s professional magazine National Defense about a lack of formal channels to guarantee funds. When the maritime militia was assigned to a task, he pointed out, funding took the form of “the county paying a bit, the city compensating a bit, and the province subsidizing a bit.” This meant that “the more tasks you perform, the more you pay.” Given the fiscal strains, local authorities have forcefully lobbied Beijing for more money. The localities also see the outpouring of central government resources as an opportunity to benefit their local fishing economies. Hainan, for example, used Beijing’s subsidies to upgrade local fishing boats and increase modernized steel-hulled trawlers under the banner of “sovereignty rights via fishing.” In fiscal year 2017, the province received 18.01 billion RMB in transfer payments from Beijing to account for “the province’s expenditure on maritime administration.”

The marketization of China’s fishery sector in the reform era has compounded the organizational problems arising from this unstandardized funding model. Since Chinese fishermen are now profit driven rather than de facto employees of the state, the government has both less formal authority and less economic leverage over them.

In the 2000s, coastal provincial military districts widely reported problems in tracking and controlling registered militia fishing ships. According to a 2015 article by the director of the political department of the Sansha MSD under the Hainan Provincial Military District, surveys conducted in Hainan localities showed that 42 percent of fishermen prioritized material benefits over their participation in the maritime militia. Some fishermen admitted that they would quit militia activity without adequate compensation or justified their absence from maritime rights protection operations because fishing was more important.

In a 2018 interview with one of this article’s authors, sources with firsthand knowledge of Hainan’s fishing community noted that each fishing ship participating in maritime rights protection activity received a daily compensation of 500 RMB, a sum “too petty compared to the profits that could be made from a day just fishing at sea, and even more so when compared to the huge profits from giant clam poaching.” These financial pressures reportedly created substantial difficulty for China in mobilizing the militia during the 2014 HD-981 clash. Some fishermen even manipulated maritime militia policies to evade regulations and conceal illegal attempts to fish for endangered or protected marine species in contested waters. Notably, such activities were completely at odds with Chinese government strategy; Beijing had explicitly prohibited illegal fishing to avoid “causing trouble for China’s diplomacy and damaging China’s international image.”

Given the unclear command and coordination arrangements, funding problems, and weak control exerted on Chinese fishermen, it is difficult to assess the extent to which Chinese authorities control fishermen operating in the South China Sea. Some fishermen have collaborated with the CCG and/or the PLA in gray-zone operations, indicating that the maritime militia does exploit the plausible deniability afforded by their dual identity as military personnel and civilian mariners. However, given the evidence in authoritative Chinese-language sources, it is unrealistic to portray the maritime militia as a coherent body with adequate professional training or as one that has systemically conducted deceptive missions in close collaboration with the PLAN and CCG. Rather, the coordination seems to be, as various sources in China, the United States, Japan, and Singapore similarly characterize it, “loose and diffuse” at best. Achieving high levels of coordination and interoperability will likely “take a long time.”

PLA officers and strategists worry that the maritime militia’s status as “both civilians and soldiers” could carry more risks than advantages during encounters with foreign vessels. A scholar at the PLA’s National Defense University asks, “If the militia uses force in maritime rights protection operation, should this be considered as law enforcement behavior or military behavior, or behavior other than war?” The director of the political department of the Sansha MSD cautions that the militia’s inadequate “political awareness” and professionalism make its members “unfit for the complex situation surrounding the South China Sea rights and interests struggle.” This makes it imperative, he argues, to “make the militia consciously comply with political and organizational disciplines, regulate their rights protection behavior, and avoid causing conflict, escalation, or diplomatic spats.”

Challenges and Opportunities for U.S. Operations and Tactics

The strength of the maritime militia is its deniability, which allows its vessels to harass and intimidate foreign civilian craft and warships while leaving the PRC room to deescalate by denying its affiliation with these activities. Meanwhile, when Chinese fishing vessels—even operating solely as civilian economic actors—operate unchallenged, their presence in contested areas helps solidify PRC maritime claims. Challenging these vessels is dangerous. Weaker states, aware of Chinese fishing vessels’ possible government affiliation, might hesitate to engage with them in a way that could provoke a PRC response. Even stronger states, like the United States or Japan, might hesitate before confronting fishing boats because of the challenge of positively identifying these vessels as government affiliated.

By “defending” China’s maritime claims from foreign interference, the PRC leverages its maritime militia in support of policies that form the core of a grand strategy of “rejuvenation” and also comprise the basis for the CCP’s domestic legitimacy. At the same time, as previously suggested, the maritime militia is among the least-funded, least-organized, and often least-professional of the forces that could be employed for these purposes. The same factors that make the maritime militia a deniable force (its civilian crews and dual-use technology) also raise the risk of accidents and escalations. This is a toxic mix: due to the maritime militia’s deniability and the core interests at stake, the PRC has a high incentive to employ it, but the more frequent its operations, the greater the likelihood of interactions with U.S. vessels that could spin out of control.

Strengths, weaknesses and capabilities

These are the authors’ own assessments of the maritime militia’s current strengths and limitations as a military instrument, as well as future projections (below).

Funding: Funding is inconsistent across units and vessels, and across provinces, which rely on different budgetary channels and have different incentives to secure subsidies. Even where funding has been secured in some localities, budget constraints in others suggest that equipment standardization is a long way off. Strained budgets also restrict training opportunities, leading to inconsistency in professionalism across the force. This raises the risk of accidents and escalations.

Command and control: Strategic, operational, and tactical command and control is inconsistent across provinces and individual vessels. The command problem is structural, arising from bureaucratic competition and multiple lines of authority. The control problem is financial, as marketization has eroded individual units’ incentives to participate in militia activities that draw away from their fishing opportunities. Command and control shortcomings inhibit combat power but contribute to the militia’s core strength: its deniability.

Combat power: Fishing boats are inherently weak forces for traditional military operations. Due to their size, they are limited by sea state and lack the propulsion plants required for high-speed maneuver. Topside gear and nets, when deployed, also limit their maneuverability. Finally, fishing vessels are soft targets for naval firepower. Fishing vessels’ “weaknesses,” however, do provide some asymmetric advantages.

First, because they are cheap, fishing vessels will always outnumber warships. Deployed in high numbers using swarm tactics, small craft can pose an asymmetric threat to warships, as U.S. Navy experience with Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy (IRGCN) forces has shown. But the Chinese maritime militia consists of fishing boats, not high-speed assault and pleasure craft like the IRGCN employs. Slow speeds reduce the ability to maneuver and increase the duration of exposure to layered defense (although the vessels’ deniability could reduce the risk that they will be fired upon). Instead of a kinetic threat, Chinese fishing vessels present more of a disruptive one. Deployed in even limited numbers, fishing boats can inhibit, if not prohibit altogether, a warship’s ability to conduct towed array and flight operations (both essential for antisubmarine warfare, a critical capability given China’s growing anti-access/area denial forces in the South China Sea).

Second, fishing vessels pose a huge identification problem. As small craft, they generate minimal radar return even in clear weather and mild sea states. In addition, Chinese fishing vessels frequently do not broadcast their position in Automatic Identification System and use only commercial radar and communications technology, making them hard to identify by their electronic emissions. The identification problem is compounded in congested environments like the South China Sea, which is cluttered with commercial traffic.

For these reasons, in combat operations, the maritime militia’s primary role would likely be reconnaissance support, although some vessels have also received training in minelaying. One of the PLA’s major force modernization objectives has been development of an “informatized reconnaissance-strike capability” modeled on the U.S. military, although command and control problems continue to impede joint force operations. When providing support to the PLAN in this way, it is important to note that maritime militia vessels would qualify as combatants under international law, despite their lack of military technology.

The basic capabilities required for militia vessels to provide reconnaissance support have been widely fielded. Before joining the militia, fishing vessels are required to install equipment permitting communication with the People’s Armed Forces Department, whose purpose is to assist with the reconnaissance function. This includes satellite communication terminals and shortwave radio, which enable beyond line-of-sight communications. But without advanced sensors and the training required to use them, militia vessels will be restricted to visually identifying opposing forces. The addition of electronic-intelligence equipment would be a game changer. In that case, the appropriate gray-zone analog for China’s maritime militia vessels might be IRGCN intelligence dhows, not swarming assault craft.

Projections

Given the PRC’s continued economic growth (and increasing government revenue) and the priority placed on military modernization, a successful resolution of militia funding problems would contribute most to recurring costs like training rather than one-time costs such as equipment, much of which has already been subsidized and acquire. However, new technology purchases beyond civilian dual-use equipment would also be possible. Additional training would foster professionalism in ship handling, equipment use, and coordination. Technology and professionalism would enhance the combat power of individual units and those operating jointly, but at the cost of deniability, the militia’s core capability as a gray-zone force. Sophisticated maneuvers, visible advanced gear, or electromagnetic emissions can help U.S. and partner forces identify a “fishing vessel” as Chinese government sponsored.

Enhancing combat power would also raise the risk of escalatory incidents. For U.S. commanders making force protection decisions, the chances of misperception could increase when weapons or sophisticated technology are present on units of unknown intentions. On the other hand, these units’ increased professionalism could dampen the risk of escalation, as they might be less prone to ship-handling errors or suspicious maneuvering. Finally, while improved command and control would reduce vessels’ deniability, its effect on escalation risks is indeterminate. Individual Chinese captains might be more restricted in their decision-making, leaving less room for error. However, they might also have less latitude to deescalate depending on the priorities of higher command.

Conclusion

In the South China Sea, pending resolution of the maritime militia’s funding and organizational problems, the greatest threat to U.S. forces remains that of accidents and escalations. Accurately identifying maritime militia vessels, ideally beyond line-of-sight, is an important way to reduce this risk by providing commanders and staffs with increased decision-space. The sheer number of militia-affiliated vessels, their minimal electronic emissions and radar cross-sections, and the congestion of the South China Sea means that identification efforts to undermine the maritime militia’s deniability at scale require a bold approach. Solving the problem will be nearly impossible without the assistance of regional allies and partners.

In regions outside of East Asia, U.S. policy makers must resist interpreting China’s distant-water fishing (DWF) fleet as a traditional security instrument. These vessels are legally noncombatants, and in practical terms, their military utility is nonexistent. The more important question is whether DWF vessels, even those engaged in civilian activities, represent an effort to acclimate U.S. and partner forces to the presence of Chinese vessels (government-affiliated or not) in the Americas. The goal might be to make Chinese overfishing an accepted (if bothersome) part of the pattern of life, an activity that resource-constrained coastal nations in Latin America ignore. Ultimately, the damage wrought to local economies by illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing activities can undermine regional prosperity. Without a wholescale effort to build local nations’ maritime law enforcement capacity, this trend will pose a far greater threat to nontraditional security realms—primarily ecological and economic—in the region, and to U.S. interests there, than any military role the Chinese DWF vessels could fill.

The authors thank Ian Sundstrom and Anand Jantzen for their comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Shuxian Luo is a PhD candidate in international relations at the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), Johns Hopkins University. Her research examines China’s crisis behavior and decision-making processes, maritime security in the Indo-Pacific, and U.S. relations with Asia. She holds a BA in English from Peking University, an MA in China studies from SAIS, and an MA in political science from Columbia University.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Jonathan G. Panter is a PhD candidate in political science at Columbia University. His research examines the origin of naval command-and-control practices. He previously served as a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy, deploying twice in support of Operation Inherent Resolve. He holds a BA in government from Cornell University and an MPhil and MA in political science from Columbia University.

This article appears courtesy of Army University Press and is reproduced here in an abbreviated form. The original (including footnotes) may be found here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.