Four Steps Towards Maritime Decarbonizing Actions: Playbook Part 5

[By Mikael Lind, Wolfgang Lemacher, Jeremy Bentham, Sanjay Kuttan, Kirsi Tikka and Richard T. Watson]

UNCTAD’s latest Review of Maritime Transport shows that emissions from shipping were still increasing last year, by 4.7 per cent. Emission efficiency has increased, i.e., emissions per ton miles have gone down over the last decade, which is some positive news. However, an important finding of the UNCTAD report, building on date from Marine Benchmark, is that about half of this improvement over the last decade is due to economies of scale, i.e., not resulting from technological improvement or a switch to alternative fuels.

Decarbonisation has become a prominent theme in the maritime industry. Everyone that delves into the topic quickly realises its complexity. Removing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions swiftly at scale is an intricate undertaking. Enabling the necessary changes requires a paradigm shift in the sector’s management of change. At a strategic level, we need to move from the fixation of a ‘subsidies mindset’ that calls for compensation for climate action to a ‘growth mindset’ that focuses on capturing the holistic benefits of decarbonisation. At the political level we should keep the responsibility for public goods in mind as we cannot rely on the altruistic behaviour of companies. And at the operational level, we need to continue cost optimisation while building resilient businesses that address and manage the effects of climate change. A mix of short-term actions and long-term investments is required to achieve decarbonisation. They will both result in a positive climate impact and improved financial returns. Doing more with less is fundamental to reducing emissions and boosting profits. We anticipate that emissions-free value chains will create superior value over time, even though this may not materialise in the short term. ‘Reaching for the stars’ requires companies and governments to focus simultaneously on economic, environmental/climate, and societal value creation by applying a systematic ecosystems approach to decarbonisation.

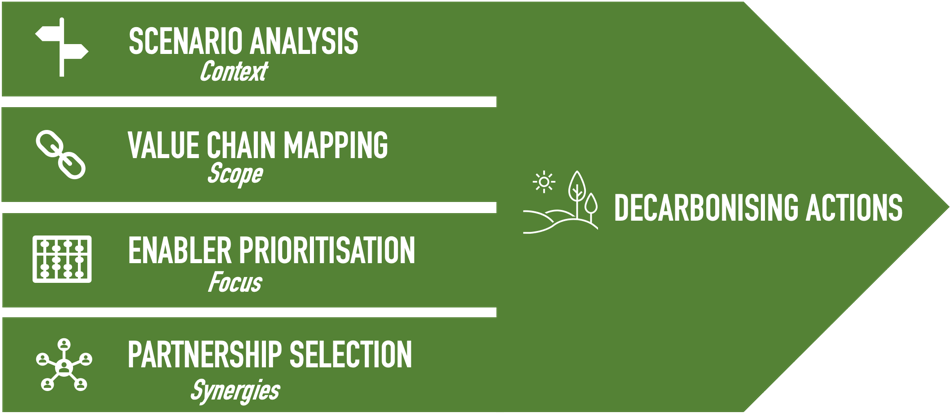

This article summarises four foundational concepts for climate action. These foundations – scenarios, value chains, enablers, and partnerships – have been explored in four preceding articles published during the second half of 2022. In this fifth article, we combine the four concepts and consolidate and convert them into a ‘4-step process’ supplemented with recommendations to guide stakeholders in their decarbonisation efforts. The four steps that drive strategies, business cases, execution plans, and decision-making are scenario analysis (context), value chain mapping (scope), enabler prioritisation (focus), and partnership selection (synergies). Although there is a natural sequence, the four steps support each other in an iterative symbiotic way of co-development. In combination, the four steps represent the 4-step path to structured decarbonising actions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: 4-step path to structured decarbonising actions

Strategies, business cases, execution plans, and ‘Go/No-go’ decisions leading to the implementation of decarbonisation roadmaps are also critical to close the cycle from intent to impact. While these management processes are usually specific to a company or country and are well covered generically in the literature, the 4-step path specific to decarbonisation is less documented. This contribution is focused on this 4-step path to structured decarbonising actions (4-step process).

Step 1 – Scenario analysis: understanding the boundaries

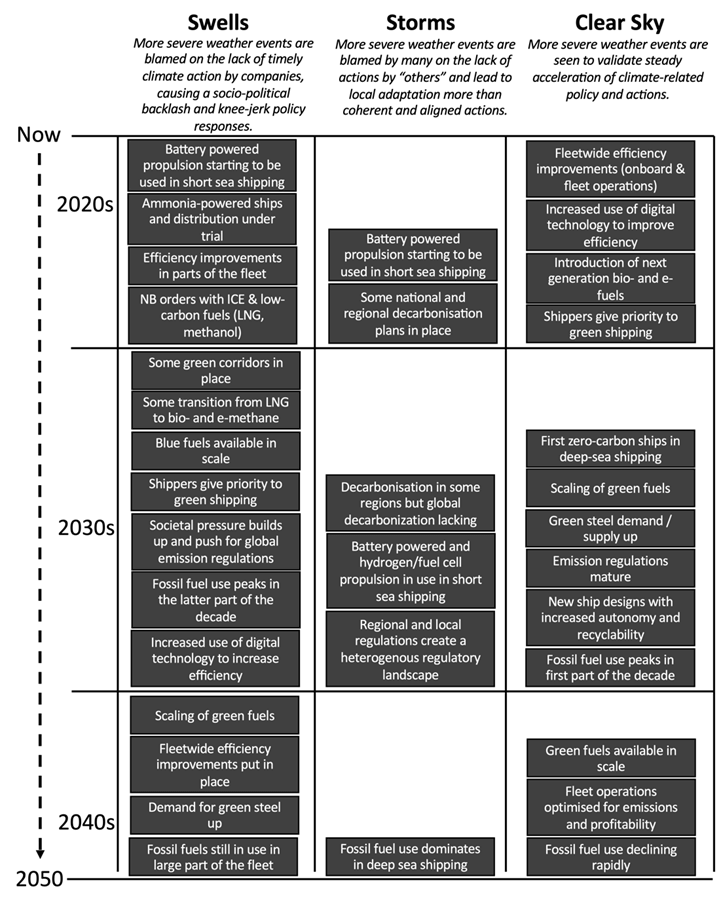

Scenarios offer plausible alternative views of how the macro-environment might develop in the long term. Scenarios are not strategies but possible alternative environments, which strategies might have to factor in to remain robust. Scenarios define boundaries that shape pathways towards different futures. Following a focused study, we developed three maritime transition scenarios: Swells places economic recovery first, Storms where local or regional interests are placed first, and Clear Sky, where competing interests and stakeholder alignments primarily drive global maritime decarbonisation. Figure 2 depicts anticipated major tipping points that will decarbonise shipping within the three abovementioned maritime transition scenarios.

Figure 2: Major tipping point moments identified in decarbonising shipping

The fundamental discovery of our study on decarbonising shipping, conducted in the first half of 2022, was that none of the specific maritime pathways that the consulted experts envisage will bring the maritime industry anywhere close to current IMO 2018 ambitions, which will be reviewed and expected to be strengthened in 2023. However, the good news is that these structured imagined scenarios are not outlooks cast in stone but are for stress testing the ways forward. They are a planning tool to adjust and refine our course of action to create the desired zero emissions future. Decarbonisation begins with outlining probable futures to define strategies that work in each of these futures and to point towards actions that may generate alternative outcomes that meet aspirations more closely.

Recommendations for future work:

- Build or review scenarios to shape or stress-test decarbonisation strategies

- Push boundaries of limiting scenarios, e.g., through pioneering actions or urging IMO member states’ governments to support the proposed “zero by 2050” plan

- Approach decarbonisation through roadmaps with detailed annual targets

Step 2 – value chain mapping: scoping the effort

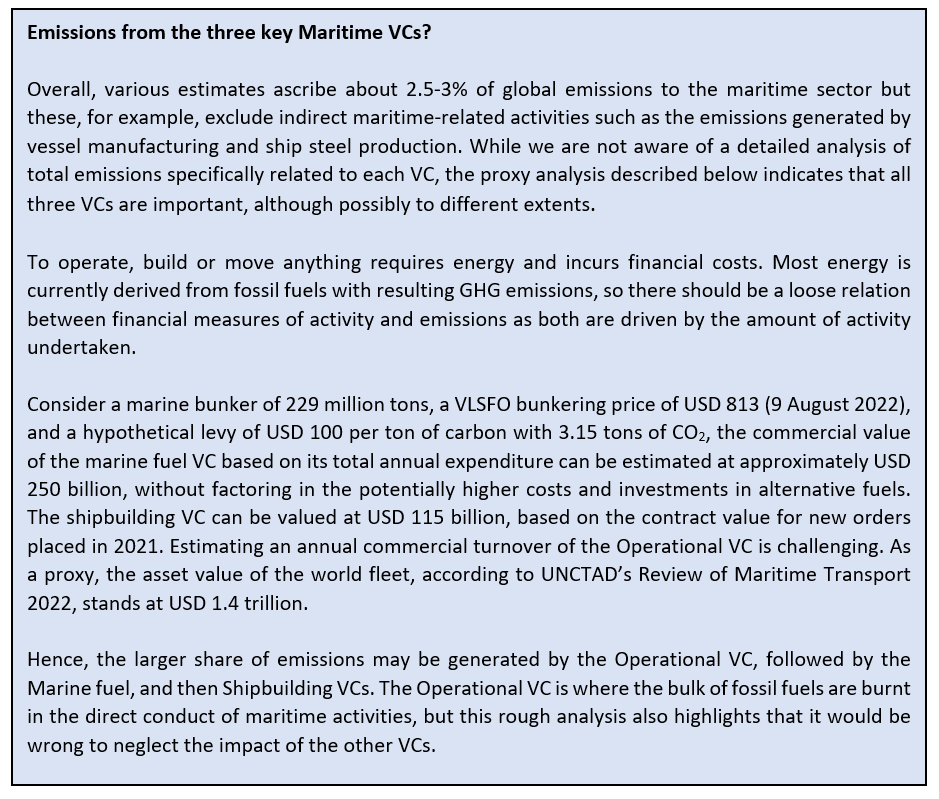

A value chain (VC) is a step-by-step business process that moves a product or service from idea to reality. Every step along the chain should add value. The value-creating activities are generally accompanied by energy consumption resulting in GHG emissions. Hence there is a critical need to analyse VCs in detail to drive decarbonisation profitably across the maritime sector and the general economy.

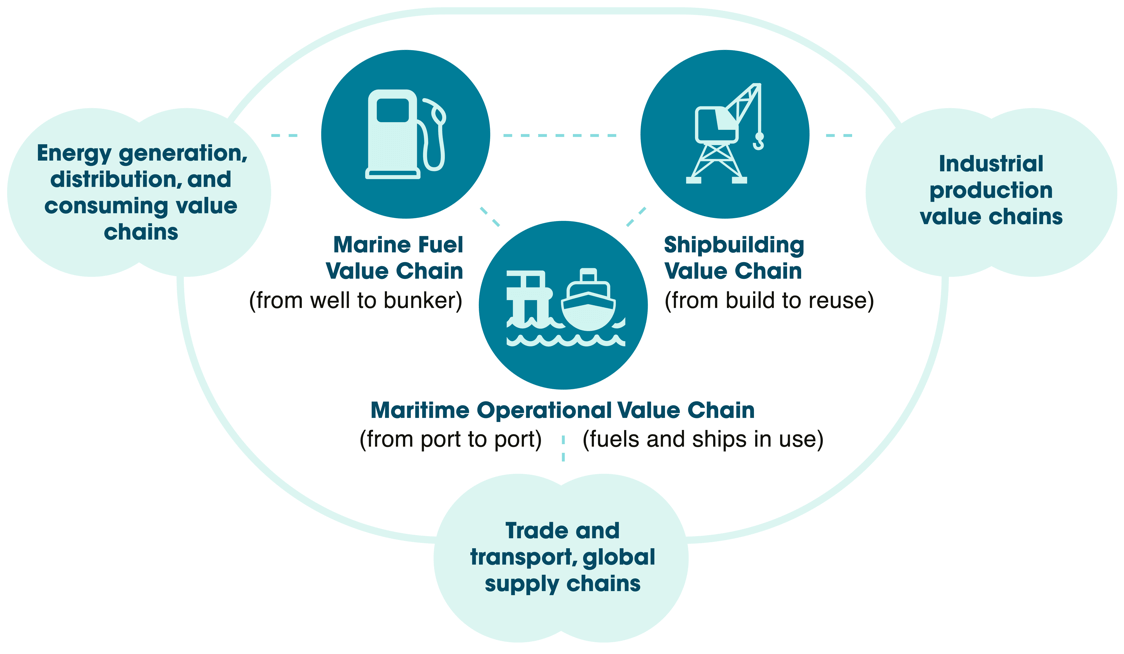

Three interdependent maritime VCs play a critical role in decarbonising shipping: Marine fuel, Shipbuilding, and Maritime operational value chains.

A detailed analysis of the split of emissions in each VC empowers companies to reduce GHG emissions in a focused and systematic way, irrespective of the VCs they are engaged in. Such an analysis is, unfortunately, not available currently and should be the object of additional research. The following box, however, indicates that significant attention to decarbonisation is required for each VC. Despite the variances in impact between VCs, each actor needs to drive decarbonisation with maximum effort to ensure that the industry reaches the current IMO 2018 ambitions. This requires commercial incentives as well as effective regulation.

Effective decarbonisation requires thinking about systems within systems. The cluster of maritime VCs is embedded in a decarbonisation ecosystem that consists of several adjacent clusters of VCs (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Interdependencies, tensions, and synergies between related value chains

Figure 3: Interdependencies, tensions, and synergies between related value chains

In this broader context of the maritime decarbonisation ecosystem, the public and private sectors need to address new challenges and opportunities. This brings about new questions. With whom does shipping compete for sustainable alternative fuels, and what does this mean for developing such fuels and decarbonising the maritime industry? What factors influence the costs of building sustainable ships and their price of adoption? How can the actors along the Maritime operational VC be motivated to align and reduce their carbon footprint? What global trade and ecosystem dynamics need to be factored into the decarbonisation calculus? Decarbonisation will remain slow until the global community has found answers to these questions, considers the greater ecosystem, aligns across the landscape of actors, and develops appropriate and effective commercial incentives.

Decision-makers in the public and private sectors need to reflect on the value chains they are engaged in and how these VCs are clustered from a decarbonisation and ecosystem perspective. They then should identify the stakeholders along those chains and build business relationships with them. This is the scope of the decarbonising actions.

Recommendations for future work:

- Map clusters of value chains relevant to maritime decarbonisation

- Identify relevant stakeholders in each value chain

- Explore mechanisms and opportunities to activate the commercial engine to align and accelerate decarbonising actions

Step 3 – Enabler prioritisation: decide on areas of focus for action

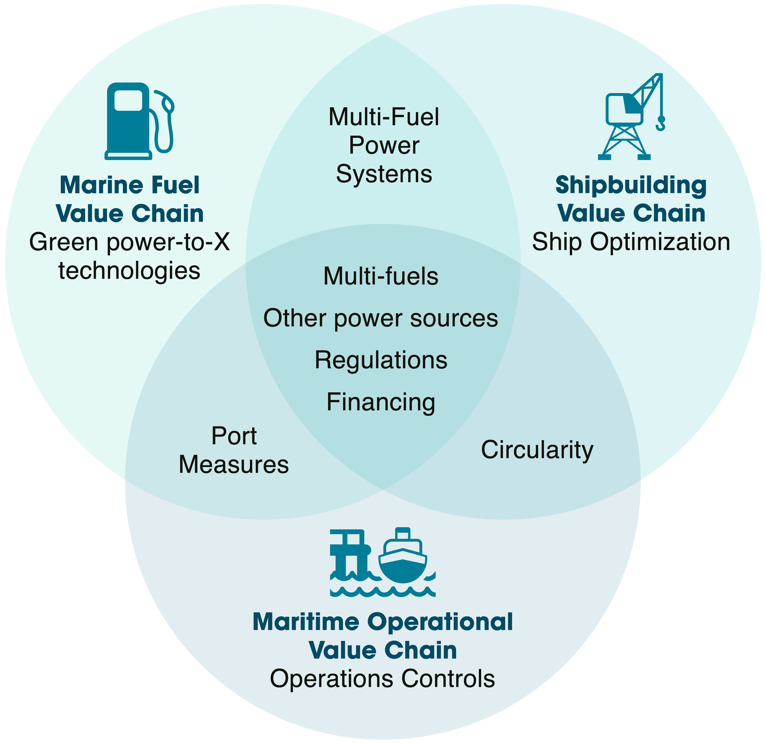

This step aims at identifying, assessing, and prioritising relevant perceived decarbonisation enablers. To reduce GHG emissions to minimal levels, the shipping industry can leverage various enablers positioned across the cluster of interconnected maritime value chains of Marine fuel, Shipbuilding, and Maritime operations. Each industry should be responsible for activating enablers within its sectorial scope. However, enablers are interdependent across an ecosystem. Hence, prioritising enablers requires a broader understanding of interrelated drivers' readiness, availability, and affordability. Some enablers are specific to only one value chain, while others cut across two or all three. Figure 4 shows a set of selected enablers with their position associated with the three interdependent maritime VCs and the cross-cutting role of some of these enablers.

Figure 4: Interdependent value chains in the maritime ecosystem

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to decarbonisation, but multiple ways should be leveraged to reduce emissions. Today, we need to bundle several enablers to achieve significant results. Even if some enablers have limited direct individual impact, the collective and synergistic impact can be significant.

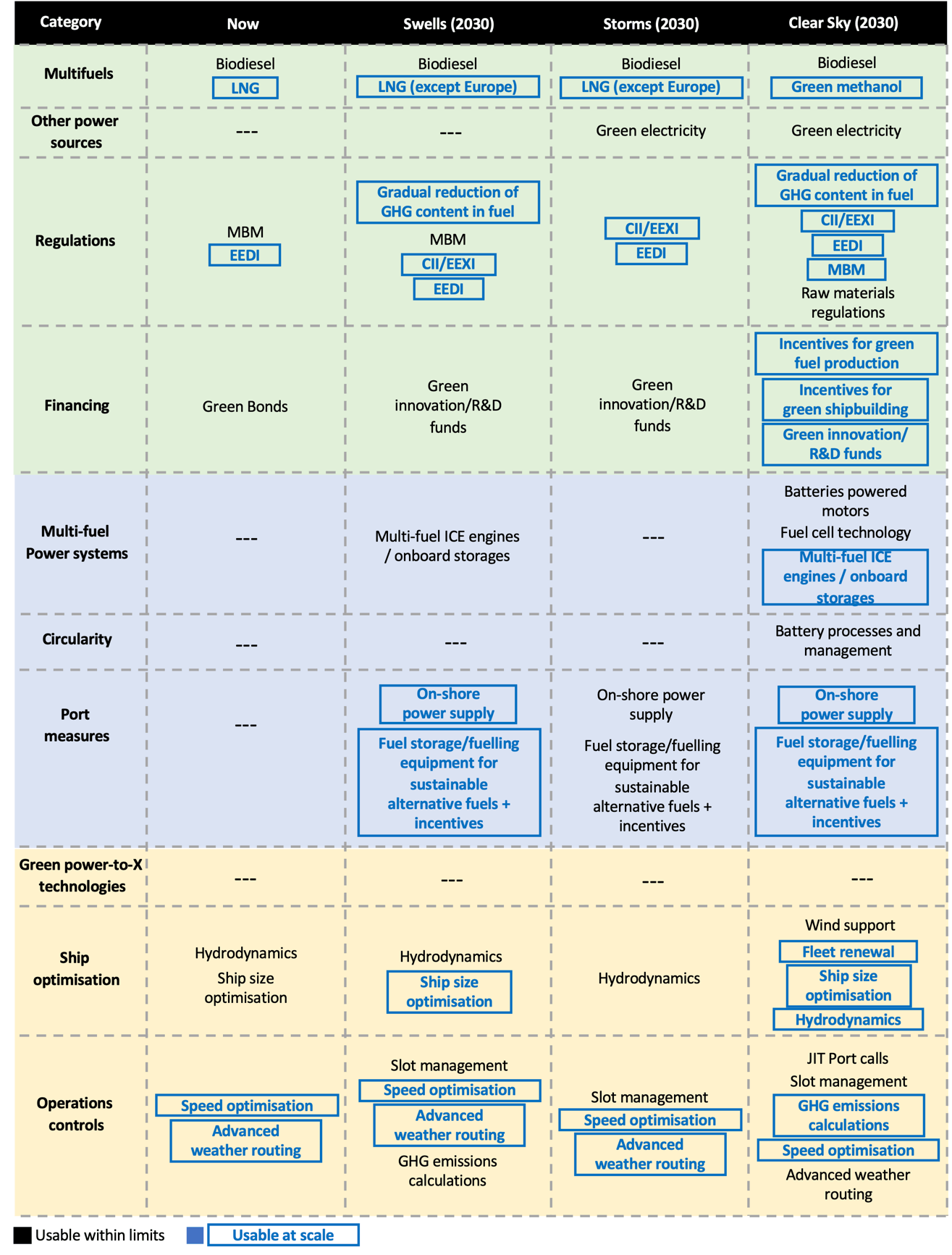

Figure 5 provides a high-level picture of the world of maritime decarbonisation now and in 2030, considering the different contextual developments in the three maritime transition scenarios: Swells, Storms, and Clear Sky. The table shows usable decarbonisation enablers at scale, which are ready, available, and affordable, and enablers that are usable within limits. Usable at scale is assumed when the readiness, availability, and financial viability of an enabler is assessed as 3 or 4 (medium to high). Usable within limits is assumed when an enabler's readiness and financial viability are assessed at 3 or 4, but the availability scores below 3 (2 = medium / low, 1 = low, or 0 = no availability).

Figure 5: Usable perceived enablers now and per scenario in 2030 (Playbook graph refined)

Figure 5: Usable perceived enablers now and per scenario in 2030 (Playbook graph refined)

As the public sector remains reluctant to dictate a direction, the private sector is in the driver’s seat. Private sector players can push the boundaries of limiting scenarios or even current global realities to go beyond the respective contextualised constraints. The public sector is essential as it has the authority to implement acceptable, transparent, and predictable policies impacting fiscal, financing and pricing mechanisms, such as a levy on high-carbon marine fuels and subsidies for low-carbon solutions. Such funds can, for example, finance retrofitting ships and decarbonisation infrastructure developments. The recent supply chain crunch has shown that a shortage of shipping supply capacity leads to extreme surges in freight rates, with a strong bearing on food security, inflation, and global value chains. Also, the energy transition can lead to shortages. Therefore, we need to provide a stable multilateral framework to avoid this shortage to occur in the coming decades. Furthermore, governments need to direct funding towards investments in ports, energy generation and distribution, and fleet renewal.

In deliberations among diverse stakeholders, multiplicity has emerged as a critical component of decarbonisation in shipping: multi-fuels, multi-fuel ship engines, and more digital operational models are core to maneuvering the multi-layered landscape of the maritime industry and the volatile nature of our world. Flexibility includes upgradable ship engines and ships, and the possibility to retrofit ships emerges as a considerable risk mitigator in the decarbonisation effort.

Public and private sector decision-makers need to understand the enablers with respect to their applicability and implications on operations. In some instances, the knowledge is already available, but needs to be established in other instances. Knowledge-building can be achieved through individual efforts. Additional research is required, commissioned by public and private sector stakeholders.

Recommendations for future work:

- Identify your relevant enablers across interrelated value chains to achieve company, industry, and ecosystem ambitions and goals

- Prioritise relevant enablers based on readiness, availability, and affordability

- Assess your ability to execute and identify gaps that need to be closed for enabler activation

Step 4 – Partnership selection: join forces

One player can activate some enablers, but collaboration between multiple actors is required in many cases. Collaboration can also help to align, accelerate, or intensify efforts. Partnerships are critical to driving decarbonisation across the larger ecosystem. Making partnerships work effectively requires strategies grounded in a profound knowledge of collaboration options.

The Maritime Decarbonisation Partnerships Matrix (Figure 6) summarises partnerships along two dimensions; first, the form of the partnership (vertical, horizontal, and diagonal), and second, the focus of the partnership and who primarily benefits (company, industry, ecosystem).

Partnerships among VCs that exclude competitors are categorised as “vertical”. Where only peers are involved, partnerships fall in the “horizontal” category; and collaborations that consist of both vertical and horizontal alignment are considered “diagonal”. Diagonal partnerships also contain overarching initiatives with (some) focus on the maritime sector. All three forms can and should ideally include governments, international organisations (IOs), intergovernmental organisations (IGOs), and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). A collaboration that primarily impacts the companies involved falls into “primarily company benefits”. A partnership that helps the entire industry, for example through building a maritime bunkering hub falls into “industry also benefits”; and an alliance that impacts multiple industries, like establishing a hub for renewable energy, which many industries can use, falls into “ecosystem, also other industries and areas benefit”.

Diagonal partnerships that directly benefit the maritime industry and the broader decarbonisation ecosystem (rectangle in Figure 6) are paramount to avoid misalignment of decarbonising actions.

Figure 6: Contemporary partnerships populated in the Maritime Decarbonisation Matrix (refined)

Reaching or exceeding the current IMO 2018 ambitions, the EU ambitions, and the Paris Climate Agreement goals requires a holistic and inclusive approach. Whilst the holistic dimension is reasonably reflected in the current partnership landscape, inclusiveness is lagging. The matrix is well populated with acknowledged partnerships, though generally, they consist of major players. Although the actions of current partnerships can have indirect positive impacts, including smaller and even minor actors, often called the ‘long-tail’ and usually struggling more than larger companies with adopting decarbonisation measures, may merit, as effective decarbonisation needs to involve everyone in a VC.

Public and private sector actors should understand the evolving partnering landscape and engage where needed. Based on what enablers they require to activate, they can benefit from selecting specific partnerships to align, close gaps, accelerate, and intensify their decarbonisation efforts.

Making partnerships work requires a collaborative culture alongside the ability to effectively compete in the market. Partnership management will be critical to driving the maritime industry towards a zero-emissions future.

Recommendations for future work:

- Select partnerships to gradually establish a portfolio of collaborations to align and cover unmet needs/capabilities at the company, but possibly also at the industry, and ecosystem level

- Ensure sufficient partnership management capabilities are developed across the organisation or accessible through partnerships

- Establish cross-value chain coordination, e.g., along zero-emissions corridors

Concluding remarks

The implications of the three explored maritime transition scenarios send a clear message. Considering the currently plausible anticipated futures and the set ambitions and goals, the maritime industry needs to act swiftly to address the climate change existential threat.

Adopting the 4-step process to structured decarbonising actions helps companies and governments to shape and intensify their decarbonisation efforts.

The first step of the 4-step process is to understand the developments outlined in plausible scenarios, which set out the challenges and boundaries with which we need to deal.

Second, decarbonising the maritime sector means reducing emissions in all related value chains. An interdependent VC perspective highlights the need for holistic cluster strategies. Cluster analysis will unveil tensions and synergies that are important for driving necessary partnerships, but it will also help in understanding the dynamics that can accelerate or constrain decarbonisation. A focus on clusters of VCs will ensure that developments are aligned. Cross-ecosystem initiatives will create opportunities across multiple sectors for sustainable growth, new jobs, and a cleaner environment for all as it mitigates risks linked to increased anthropogenic GHG emissions.

A holistic approach, and broader ecosystem thinking, will drive coordinated emissions-efficient operations (the Maritime operational VC), production of alternative fuels (the Marine fuel VC), and green shipbuilding practices (the Shipbuilding VC).

Third, decarbonisation requires the activation of enablers. Not all enablers are currently mature or available at scale; some still have a high cost of adoption. This requires the public and private sector actors to assess their relevant enablers urgently. Pioneers can initiate changes that build competitive edge and encourage responses from competitors – creating virtuous cycles as increasing deployment drives down costs. In addition, fertile ground for development can be prepared by funding initiatives. A recent example is an announcement by CMA CGM of a USD 1.5 billion special fund to accelerate the energy transition in shipping and logistics. At the political level, the European Parliament has voted in favour of including shipping in the Emissions Trading System (ETS) and “75% of the revenues generated from auctioning maritime allowances shall be put into an Ocean Fund to support the transition to an energy efficient and climate resilient EU maritime sector”.

Collaboration is the fourth and final step of the 4-step process before stakeholders can progress to individual strategising, business case design, execution planning, and ‘Go/No-go’ decision-making. Many decarbonisation partnerships have emerged that cover the necessary diversity of activity, but there is a need to make them more inclusive by including the long-tail players. Here, technology enables the involvement of smaller actors through platforms and new open-innovation approaches.

Finally, without some form of common regulation and private sector alignment, decarbonisation of shipping will remain slow. Hence, we call for developing and shaping the active and collaborative global multi-stakeholder ecosystem that will help the industry to abate shipping and contribute to decarbonisation efforts across the entire economy.

We end this article by calling out the most important recommendation. Our overall self-interest is to avoid the exponential costs of decarbonisation and the environmental/climate threat. We can build competitive advantages by kick-starting the commercial engines that drive the decarbonisation of VCs. The ‘4-step path to structured decarbonising actions’ provides a critical foundation in addressing the challenges head-on for this large hard-to-abate transport sub-sector. Captains of industry and political allies need to “Act Faster Together” now!

About the authors

Mikael Lind is the world’s first (adjunct) Professor of Maritime Informatics and is engaged at Chalmers, Sweden, and the Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE). He serves as an expert for World Economic Forum, Europe’s Digital Transport Logistic Forum (DTLF), and UN/CEFACT. He is a well-recognised trade press author, the co-editor of the first two books of maritime informatics, and co-author of the recently released Practical Playbook for Maritime Decarbonisation.

Wolfgang Lehmacher is operating partner at Anchor Group and advisor at Topan AG. The former head of supply chain and transport industries at the World Economic Forum, and President and CEO Emeritus of GeoPost Intercontinental, is advisory board member of The Logistics and Supply Chain Management Society, ambassador of The European Freight and Logistics Leaders’ Forum, advisor of GlobalSF, and co-author of the recently released Practical Playbook for Maritime Decarbonisation.

Jeremy Bentham is the Co-Chair (Scenarios) at the World Energy Council and a retired member of strategy leadership team at Shell. A leading scenarios expert, he was previously Head of the Shell Scenarios Team and Vice President of Global Business Environment at Shell International.

Dr Sanjay Kuttan is currently the Chief Technology Officer of the Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonisation. He has also been with the Singapore Maritime Institute and the Nanyang Technological University. His experience in the private sector has primarily been in the oil and gas, as well as energy sectors. He also serves as a council member of several Energy related Associations.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Kirsi Tikka has over 30 years of shipping experience, member of several boards and advisor to maritime start-ups, former Executive Vice President of American Bureau of Shipping.

Richard T. Watson is a Regents Professor and the J. Rex Fuqua Distinguished Chair for Internet Strategy in the Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia. He has published over 200 journal articles and written books on electronic commerce, data management, and energy informatics. His most recent book is Capital, Systems, and Objects.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.