Enhancing Voluntary Weather Observations From Ships in the Arctic

The Arctic Ocean is a hot spot in global climate change. The Arctic region has experienced three to four times more warming than the Earth on average. This has been reflected in thinning and shrinking of the sea-ice cover, lengthening of seasonally ice-free periods and ocean warming during summer stage. These changes are most apparent in the Arctic coastal seas where most of the human activity takes place.

Consequently, Arctic shipping has increased. According to the Arctic Council’s PAME working group, ships entering the Arctic waters increased by 25 percent between 2013-2019. Most of the ships are commercial shipping vessels and bulk carriers, but an increasing number of tourist vessels are sailing in the Arctic as well.

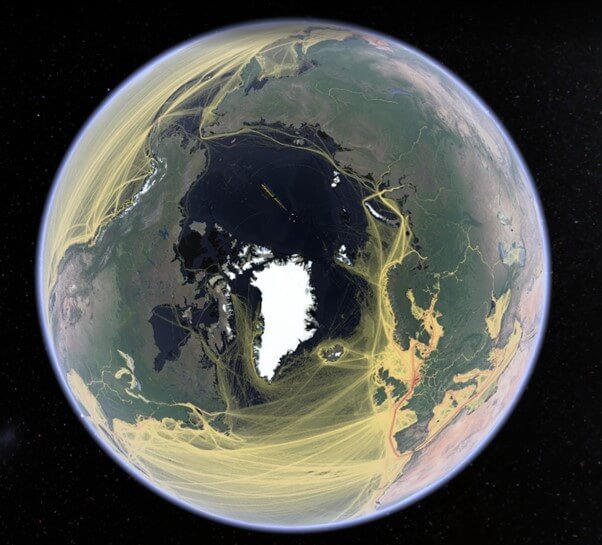

Tracks of ships based on global AIS data in the Northern Atlantic and Arctic Ocean in 2020 (Courtesy of Jukka. Pekka Jalkanen/FMI)

The state of the Arctic Ocean is monitored by satellites, airborne measurements, automatic weather stations, surface buoys, ocean moorings and research expeditions. However, the present monitoring network has been designed to serve mainly for climate monitoring purposes. In particular, the real time observation network is very sparse compared to other sea areas due to difficulties to maintain automatic systems in the harsh polar conditions.

Voluntary meteorological and oceanographic observation from ships sailing the oceans has a long heritage. However, only a few ships navigating in the Arctic are collecting environmental data. There is a huge potential for commercial ships to act as platforms for environmental measurements and fill the gap in monitoring the state of Arctic coastal seas.

Benefits – Why it is crucial to continue and enhance voluntary observations in the Arctic Ocean?

Obvious benefits of ship-based measurements in the Arctic are that they provide vital in-situ measurements in areas where meteorological-ice-ocean information is limited or totally lacking. The sharing of observations allows all operators navigating in the same sea area to be better and more equally informed. Furthermore, observations are used in ice services and assimilated to weather models. This would considerably improve the overall quality of ice charts and forecasts contributing to safe operations in the Arctic Ocean and beyond.

This data is not only necessary for the safety of navigation but is also crucial for calibration of satellite data and for validation and verification of numerical models. While research expeditions in the Arctic Ocean only cover localised areas during very limited periods, the shipping traffic in the Arctic can contribute to continuous data acquisition in a variety of routes.

Finally, European, and North American countries have committed to an open data policy. All measurements, satellite data and forecasts produced by the governmental agencies and research bodies are basically made freely available and easily accessible, to enhance entrepreneurship, innovations, and scientific discoveries. Adding the data provided by the marine industry to that palette would certainly boost the development of industrial applications for route optimisation, emissions reduction, and risk management.

Solutions – How to contribute to environmental data collection in the Arctic Ocean?

Ship owners can contribute to environmental data collection in the Arctic Ocean in three ways:

- by sharing the environmental data collected for navigational purposes,

- by collecting visual observations,

- by installing additional automatic measurement systems.

1) Sharing of environmental data collected for navigational purposes:

While many ships are already collecting meteorological and basic oceanographic data for navigational purposes, this data is usually stored on a local computer on the bridge. Instead, this data could be automatically sent to data server, therefore contributing to the monitoring of the Arctic Ocean. One solution is to utilise the European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet) which is an infrastructure to harvest and disseminate marine data. EMODnet has developed tools for digesting any publicly available data sources.

The EMODnet Data Ingestion portal facilitates the ingestion of marine datasets for further processing, as well as the publication as open data. It ultimately contributes to the development of services for society. It primarily focuses on data sets that are not yet handled. EMODnet data is used globally by forecasting centres and research institutes. It also provides a portal to visualise Arctic observation.

Bathymetry data is also needed from the Arctic Ocean. To this end, the International Hydrographic Organisation (IHO) is coordinating crowdsourced bathymetry (CSB) collection of depth measurements from vessels. Observations are based on standard navigation instruments, while they are engaged in routine maritime operations. CSB is a valuable tool that can supplement the more rigorous and scientific bathymetric coverage done by hydrographic offices, industry, and researchers around the world.

2) Collecting visual observations:

To date, there is no automatic measurement of sea ice characteristics. Vessels operating in ice-infested waters could implement a visual ice observation scheme where officers on bridge are taking notes on ice conditions according to the “Ice Watch” protocol. The observations are sent by email to a database. Ice observations are then displayed in real time on the Ice Watch website, available to all users.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) Voluntary Observing Ships‘ (VOS) scheme recruits ships for taking and transmitting meteorological and sea surface observations such as surface wind speed and direction, air temperature, humidity, sea surface temperature, atmospheric sea level pressure, clouds, wave and swell parameters and weather information. The programme provides high quality data and the setting up of the system is usually conducted by National Meteorological Services or by local Port Meteorological Officers.

3) Installing automatic ocean monitoring systems on board:

Surface ocean measurements need the installation of a “FerryBox” automatic ocean monitoring system on the inlet of the cooling water system. The “FerryBox” measurements have been deployed very successfully in various vessels operating in Europe and North America but the only operational system in the Arctic is installed on one vessel transiting between Tromsø and Svalbard.

Conclusion

The driving principle of ship-based measurements is that data should be freely available to the public. Considering the open data policy adopted by a vast majority of governmental agencies and research bodies in North-America and Europe, it is clear that failing to add the data coming from the marine industry would be a great and damaging waste. A data-sharing agreement between ship owners and established international bodies such as WMO, IHO or EMODnet would facilitate this effort, thus multiplying societal benefits of voluntary environmental observations in the Arctic Ocean.

Jari Haapala is head of the marine research unit at the Finnish Meteorological Institute.

Christine Valentin is executive director for World Ocean Council Europe.

Veronica Willmott is a project manager / science coordinator at the Alfred Wegener Institute.

Acknowledgements: Science-Industry cooperation is part of the EU funded project ARICE (www.arice-h2020.eu) EU grant agreement number 730965.

Points of contact

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.