Container Shipping: Mixing up Size with Growth

While there seems no end to the technological economies of scale in container shipping, the question is whether building ever bigger ships serves a purpose, for the firm itself and for society at large. In the process of scaling up, liner operators are mixing up size with growth.

Big is no longer beautiful

Talking about vessel sizes of 20,000+ TEU nowadays not only brings admiration. Year-on-year growth in TEU capacity has led to overcapacity and deterioration of freight rates. For 2016, Drewry expects another year of losses for the industry. Increasingly industry watchers wonder whether a container ship will ever reach a maximum size at all. Does this make sense for the owner or operator? Does it make sense from a society as a whole?

Container shipping has been a game of big players because of its capital intensity, geographical scale and the sheer volume of world trade. Main hubs and spokes, allow liner operators to balance efficiencies on the long haul with frequent calls to a large number of ports with feeder services.

The footloose and international nature of the industry allows liner operators to raise funds on international financial markets, choose a flag to their convenience, charter vessels for additional capacity and flexibility, and man ships with cheap but competent officers and able seamen from countries like Philippines, Indonesia, Ukraine or Latvia.

Operating in international waters even allows them to deploy redundant ships elsewhere or get rid of overaged tonnage on faraway beaches. These market characteristics made liner operators go for business models based on economies of scale because building bigger ships brings down operating unit costs.

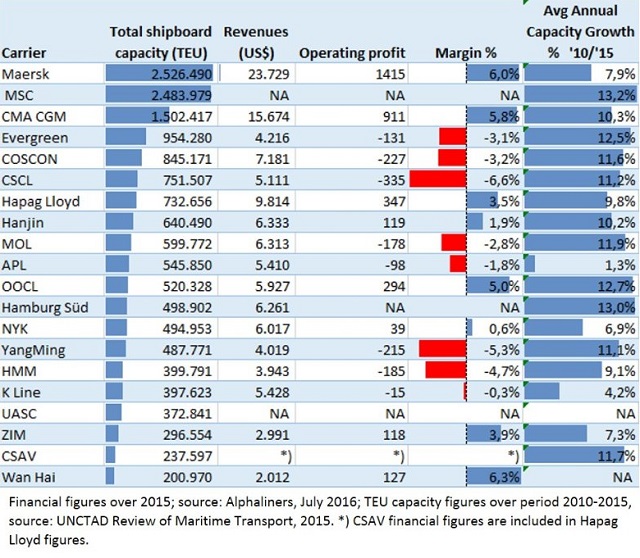

However, where trade volume has witnessed a year-on-year growth of five percent, compound annual rates of TEU capacity has been a consistent rate of seven percent for five and ten-year periods since the beginning of this decade (Dynaliners Trade Review, 2015).

The below table shows the TEU capacity increase for the major carriers.

To answer the question whether larger vessels still make sense, we ought to build an understanding on the theory of the growth of the firm. This places the strategic moves of today’s global liner operators into commonly understood principles of business growth strategy.

To answer the question whether larger vessels still make sense, we ought to build an understanding on the theory of the growth of the firm. This places the strategic moves of today’s global liner operators into commonly understood principles of business growth strategy.

Theory of the Growth of the Firm

Let's review one of the classics in business strategy: the Theory of the Growth of the Firm by Penrose[i]. She rightfully places firms in the middle of society. The firm is a vehicle for society to efficiently allocate resources (manpower, capital, expertise, management capabilities) to economic activities in such a way that not only firms grow, but that also society is allowed to benefit from the firm's capabilities to offer cheaper and better products and services.

Penrose's theory centers around the notion that the firm is a collection of productive resources, tangible and intangible, fixed and flexible, disposable and durable resources that can be put to use into a production process and can thereby expand the business. However, as we talk about resources, the assumption is that the use of these resources is limited by quantity, capability and time.

Secondly, when operations grow, they also require more managerial and administrative capabilities to control them. In simple terms: the span of control becomes larger as the firm grows, and administrative overhead can become a burden for the firm. Thirdly, firms and the engineers working for them are continuously searching to better utilize these resources or replace them by better, different resources. This drive in itself makes firms to continue to search the boundaries to grow, both in size as well as in profit.

In summary, the economies of larger firms are the following:

.png)

Source: Penrose, theory of the growth of the firm

In container shipping, the economies of scale come from technological economies of container ship designs that allow more container slots (jargon for a container position) on a vessel. Larger firms also benefit from managerial economies, for example by spreading of overheads over large scale operations, leveraging investments over ICT systems, having access to vast financial reserves and acquiring cheap capital for further investments.

In shipping terms economies of expansion means that companies who are better in gaining efficiencies from adding new capacity to the existing fleet of vessels are better positioned to grow market share as well as offer a more frequent sailings, and/or include more ports by adding vessels in new trades.

Size is not equal to growth

The UNCTAD Review of Maritime Transport statistics of the largest liner operators it shows that the top five operators have gained market share in past years from 35 percent in 2010 to 45 percent in 2015. This indicates that larger operators have been more aggressive in expanding their container capacity than smaller operators.

However, expansion may in principle lead to resources being used more efficiently, nevertheless we have to be critical and assess the returns on assets. A successful expansion is not measured by the sheer capacity which liner operators have afloat but by the growth of the firm, i.e. sustained profitability.

Secondly, we have to distinguish largest liner operators from smaller ones. What may work as a successful expansion strategy for the larger operators, may not be wise for the smaller operators, who often deploy vessels in smaller and quite different trades. When bigger ships enter the market in main trades relatively smaller ships cascade down to smaller trades. For large operators, adding bigger ships puts more weight in the scale both in main as well as in smaller trades.

The result of the process of rapid capacity expansion is that the industry has been that returns on net operational assets across the board have significantly lacked behind (PwC Shipping benchmarking report 2014). The key message here is that vessel size is not necessarily an indicator for growth, obviously not for the smaller operators and I dare to say it is no longer for the larger ones either. There is even an indication to the limitation of the economies of expansion from a society point of view when resources such as financial capital are wasted in a loss-making business, or when ships are scrapped at a very young age.

Liner operators captured in lock-in strategy

We have now arrived at the essence of the Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Economies of growth occur when internal economies are available to an individual firm which makes expansion in particular directions - new markets, new trades, new services – profitable. This is good for the firm as well as for society.

What we witness in container shipping is that economies of scale do not provide economies of growth (a return on their investments). Looking at the statistics again, we can conclude that only the top ranked liner operators have been able to benefit from expansion and grow market share.

Increasingly fewer operators can keep up. They have not been able to get a positive return on their assets, lost profitability and lost market share or had to be rescued by banks or governments. Their negative year-over-year return on capital employed and operating profit margins indicate that economies of scale do not grow their business.

Hyundai Merchant Marine (HMM) is a clear example how cheap capital (and some government intervention) fuelled its expansion strategy. HMM suffered from year-over-year negative profit margins (-6.1 percent in 2015) and failed to return investments on capital employed (-6.27 in 2015). Recently it was announced that a Korean bank will take over the company with the aim to improve its financial situation and clean the sheets to enable HMM to be part of the 2M alliance.

Basically what we are witnessing is a lock-in effect into the dominant strategy of an industry, while financial performance is weakening. Increasingly fewer liner operators are able to hold on to the economies of scale strategy, but neither the big players nor the smaller players can afford to deviate from the strategy of building bigger vessels.

Reaching the point of no return

Following the above logic we arrive at the conclusion that the container shipping industry is mixing up size and growth. When expanding capacity, mega vessels are to be financed. The business for these vessels still proofs to be positive– considering the full order books of the liner operators – based on the principle of lower unit costs and consequentially lower operating expenses.

At the same time it must be realized that there is a push from (Chinese) shipyards in need for discounted newbuilding orders as well as a pull from non-asset owners who have access to cheap (Chinese) capital, that is now replacing the long standing KG System.

However, more tonnage leads to under-utilization of existing assets and deteriorates their return of investments of existing assets, and thereby the ability to grow the business. These economies of scale of larger vessels lead to a negative side-effect where redundant ships are sold off to second hand markets, cascade down to smaller trades, and eventually to scrap market. This kind of asset play impacts both return of capital employed for existing smaller vessels and profitability of the industry across the board.

Where the primary focus for industry leaders have always been on size of new assets, focus of the followers are to be drawn on sustaining value and deviate from the dominant 'big is beautiful' industry strategy. It takes courage to move away from it, but may save these firms from becoming second hand news.

The same may hold true for big players in the long run. Industry leaders seem to be able to grow with increasing vessel size, but find themselves on a point of no return. These companies make themselves more vulnerable for slowdowns in world economy and have to be prepared to overcome longer periods of rock-bottom low freight rates. Nothing but more trade can save these liner operators from a loss making strategy. In the meantime, selling off assets and forming of new alliances is the only temporary solution to cut down on operating expenses and sit out the weak market.

As long as liner operators cannot reinvent their place in society, where the growth of the firm equals adding value to society, it is reshuffling of the same cards with fewer but bigger players, while smaller ones are roaming around to win a penny elsewhere. In today’s day and age, financing new capacity with cheap capital is a waste of resources and is ruining entire shipping markets.

[i] The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, (1995), Edith Penrose, Oxford University Press, first published in 1959

Maurice Jansen works at STC-Group at the Innovation, Research & Development department. He lectures at Netherlands Maritime University and is a visiting researcher at Erasmus University Rotterdam.

This article is written on personal title, with the support of shipping industry expert Mr Theodor Strauss.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.