Norway Clarifies Svalbard Treaty After Russian Complaint

Norway's Minister of Foreign Affairs Ine Eriksen Søreide and Minister of Justice and Public Security Monica Mæland have clarified the nation's stance on the Svalbard Treaty as it enters its 100th year.

The move apparently comes as Russia voices its concern over limits being put on its operations there, including coal mining and fishing.

The Treaty

On February 9, 1920, Norway and eight other countries signed the Svalbard Treaty (originally the Spitsbergen Treaty) in Paris. The Treaty entered into force in 1925, and Svalbard became part of the Kingdom of Norway. The treaty, now with nearly 50 signatories, sets out that:

• Spitsbergen is under Norwegian administration and legislation.

• Citizens of all signatory nations have free access and the right of economic activities.

• Spitsbergen remains demilitarized. No nation, including Norway, is allowed to permanently station military personnel or equipment on Spitsbergen.

The situation in the archipelago before 1920 has been likened to the Wild West, full of adventurers, coal miners, gold diggers and fortune hunters taking the law into their own hands. But once Norway’s sovereignty was formally recognized, it was possible to resolve property ownership issues and bring unregulated activities under control.

Many countries wanted to ensure that the Svalbard Treaty did not put an end to all foreign activity in Svalbard, so the principle of equal treatment was enshrined in the Treaty. This means that, in certain areas, Norway is obliged to treat nationals and companies from states that are party to the Treaty in the same way as Norwegian nationals and companies. They have, for example, an equal right of access and entry to the archipelago and equal rights to engage in fishing and hunting and other commercial activities.

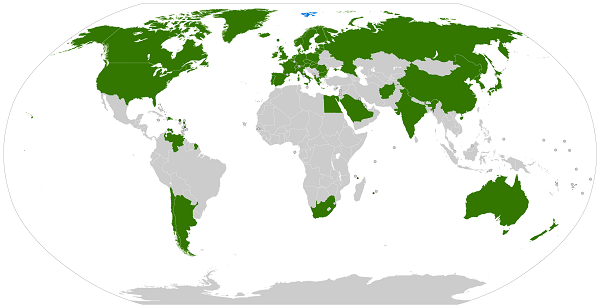

Svalbard Treaty Signatories

Russia's Complaint

Earlier this month, Russia's Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation Sergey Lavrov sent a message to Søreide calling on Norway to ensure "equal free access" to the archipelago and the possibility of conducting economic and economic activity there "on conditions of complete equality."

Lavrov notes Russia's concern about restrictions imposed on the use of the Russian helicopter [associated with Russia's coal mining activities on Svalbard], the establishment of a fish protection zone by Norway and “the artificial expansion of nature protection zones to limit economic activity in the archipelago.”

“On Svalbard, Russia - the only one except Norway - has been carrying out economic activities for many decades and does not intend to curtail its presence. On the contrary, there are long-term plans for its strengthening, diversification and modernization.”

Lavrov has requested bilateral consultations to remove the restrictions.

Norway's Stance

“Norway has given high priority to fulfilling these obligations under international law ever since the Treaty was signed,” said the Ministers. “It is worth mentioning that the provisions on equal treatment in the Svalbard Treaty are far less extensive than the corresponding provisions of the European Economic Area Agreement.”

According to Norway, the waters outside the 12 mile zone, but within the exclusive economic zone (200 miles) are waters where Norway can limit the rights of any third party. This has been disputed by countries with interests in fisheries and oil and gas including Latvia and Russia.

The Ministers state that provisions on equal treatment apply only to nationals and companies from states that are parties to the Treaty. Traditionally, however, Norwegian law in Svalbard has not made a distinction between nationals from contracting parties and nationals of other states. This means that people from a country like Thailand, for example, have enjoyed many of the same opportunities as citizens from states that are parties to the Treaty.

“The right to equal treatment is not the same as the right to resources. The Norwegian authorities can both regulate and prohibit activities, as long as there is no discrimination on the basis of nationality. This is particularly important when we take action to safeguard Svalbard’s vulnerable environment or share limited resources.

“At the same time, the Treaty does not preclude differential treatment on grounds other than nationality. For example, it is only people resident in Svalbard who are entitled to hunt reindeer in the archipelago. And only permanent residents of Svalbard are allowed to own cabins there. Likewise, only vessels from countries that have traditionally harvested prawns in the area are entitled to catch prawns in the territorial waters of Svalbard.”

Certain states have challenged Norway’s interpretation of the Treaty’s provision on equal rights to engage in fishing and hunting. Under the Treaty, ships and nationals from states that are parties to the Treaty have equal rights to engage in fishing and hunting on land in Svalbard and in the territorial waters around the archipelago, i.e. up to 12 nautical miles from land.

Nevertheless, the E.U. has cited the Treaty’s principle of equal treatment when, for example, the E.U. member states Latvia and Lithuania have expressed an interest in harvesting snow crabs on the Norwegian continental shelf far beyond the territorial waters of Svalbard.

“But the wording of the Treaty is clear,” said the Ministers. “The provisions on equal treatment apply only in Svalbard’s land areas and territorial waters. We see that certain other states could have a clear interest in advocating a more expansive interpretation to include areas beyond the territorial waters. However, any such interpretation would mean an expansion of their rights at Norway’s expense.

“States that claim that the reference to territorial waters in the Treaty also includes sea areas outside the 12-nautical-mile limit are interpreting this provision in a way that is contrary to international law. This is clear not only from the Svalbard Treaty, but also from the Law of the Sea and the Vienna Convention on the law of treaties.

“The fact that there can be differing interpretations of the same provision of a treaty is a more general problem, and the Svalbard Treaty is a case in point. Misunderstandings or a lack of knowledge about the actual substance of the Treaty can also in some cases lead to unrealistic expectations or opinions about the Treaty’s significance for the interests of specific stakeholders.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

“Svalbard is part of Norway. Norway does not routinely consult with other countries about how it exercises authority over its own territory.”