How the Fishing Fleet Served the U.S. Coast Guard in WWII

[By J. Edwin Nieves, public affairs officer, Coast Guard Auxiliary Division 6]

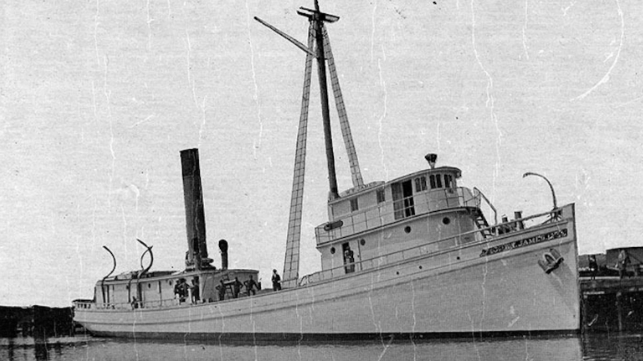

In the early days of World War II, demand skyrocketed for vessels to fill the needs of the U.S. sea services. The Coast Guard was no exception as they competed with the U.S. Navy and U.S. Army for new construction as well as privately owned ships. Facing a high demand for vessels, the service turned to the U.S. fishing industry as a source for its cutters. These emergency acquisitions included East Coast trawlers, whalers from both coasts, and East Coast menhaden fishing vessels, such as the Emergency Manning vessel Dow (WYP 353).

During World War I and World War II, the menhaden fishing fleet became a ready reserve for the Navy and Coast Guard. Both services needed small, shallow draft vessels for coastal convoy escort, mine planting, minesweeping, and anti-submarine net tending duty. Many of these vessels were purchased or leased, while others were loaned to naval forces by fishing businesses as their contribution to the war effort.

Menhaden fishing vessels were designed to harvest schools of small fish in coastal waters, primarily in the Chesapeake Bay. Their very long and narrow design sported a distinctive plumb bow, elevated pilot house to spot large fish schools, a center hold to store the catch and low freeboard to haul full fishing nets on board the vessel. The ungainly design of these vessels was well suited to harvesting large quantities of fish in sheltered waters, but not high seas combat operations.

The Coast Guard patrol vessel EM Dow, formerly the Menhaden-type fishing vessel Annie Dow, was a wartime acquisition under charter (lease) by the Coast Guard. Vessels like the Dow were given the prefix “EM” for “Emergency Manning.” In preparation for military service, these fishing vessels were armed with one or two one-pound cannons fore and aft. This addition usually required sections of iron plating on the deck, which added to the pilothouse and parts of the superstructure for crew protection. Additional communications gear and combat equipment contributed to making the cutter top heavy. These additions had a negative impact on the stability and sea-keeping qualities of these would be fighting vessels. In World War I, the USS James, a menhaden fisherman converted to Navy minesweeper, capsized in a gale off the French Coast.

The Dow was 134 feet in length, nearly 22 feet wide with a draft of 11 feet—typical dimensions for a menhaden fisherman. After conversion to military service, Dow’s gross tonnage increased to over 240 tons with a complement of 37 officers and men.

In June 1943, EM Dow entered Coast Guard service at the Baltimore Naval Shipyard under the command of Lt.j.g. Edward Doten. The Navy assigned EM Dow to the Eastern Sea Frontier based in Norfolk, Virginia. Soon after entering service, the ungainly cutter was re-assigned to duty as part of the Navy’s Caribbean Sea Frontier. Late in the summer of 1943, it traveled down the East Coast, crossed The Bahamas island chain and arrived at its new homeport of San Juan, Puerto Rico.

From San Juan, the Navy assigned Dow to patrol the western coast of Puerto Rico. The cutter focused mainly on the approaches to the port of Mayaguez and the Mona Channel, an important commercial waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Caribbean Sea. The Dow performed anti-submarine patrols and escorted commercial vessels in coastal Caribbean oil and bauxite convoys. It also provided search and rescue support for the U.S. Army Air Corps’ Ramey Field in Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, current site of the Coast Guard’s Borinquen Air Station.

Early in October 1943, a tropical storm began brewing along the equator to the southeast of Puerto Rico. Later know as Hurricane San Calixto, the storm reached Category 2 strength on the Saffir-Simpson wind scale and began swirling to the northwest toward the Windward Passage.

Early on Oct. 13, 1943, the Dow received orders to proceed south of Mona Island to meet the Coast Guard Cutter Marion. Had the local naval command understood the seriousness of the weather conditions, the mission might have been aborted. The weather quickly deteriorated as the Dow headed on a collision course with the storm’s path. As the Dow closed with the hurricane, Doten ordered a series of maneuvers and course changes to avoid the heavy seas, but later altered course to steer the old fishing vessel’s high bow directly into the towering waves.

The vessel’s narrow beam and low freeboard were no match for the hurricane’s high winds and heavy seas and by the afternoon of next day, the Dow began taking on water. First the cutter lost electricity and radio communications and then its engines failed. After using a hand-held blinker to signal the Marion that he was taking on water and in need of assistance, Doten gave the order to abandon ship. The Dow was abandoned about a quarter mile south of Punta Higueros, Puerto Rico, before winds and heavy seas ran it aground. All of Dow’s 37 crewmembers were ferried to the safety of the Marion.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

In 1996, the Naval Historical Center conducted a survey to identify wreck sites in Puerto Rico. It located a wreck in northwest Puerto Rico directly across from Punta Higueros on the eastern shore of Desecheo Island. The wreck lies in 30 feet of water in an area known locally as “Tornado Cave.” Further research into this site could confirm the wreck’s identity and whether or not it is the Dow. A search through several databases, including Puerto Rican newspapers has not identified any other maritime accidents in that location.

Although records indicate that the Coast Guard sold EM Dow’s submerged hull to a local salver in 1948 for fittings and usable equipment, location of the vessel’s final resting place remains unconfirmed. Regardless of its exact location, the fishing vessel and Coast Guard cutter builders would never have imagined the Dow would meet its fate so far from its Chesapeake Bay home.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.