The Annihilation of German Single Ship Companies

Op-Ed by Erik Kravets, co-founder of legal firm Kravets & Kravets

Over the past decade, Germany became one of the largest shipowning nations in the world (specifically, it is presently number four, after Greece, China and Japan). One of the reasons why this happened was the influx of capital into newbuildings, driven forward by the funding model that became popular beginning around 2004. Single ship companies (Kommanditgesellschaften, or limited partnerships) coupled with the tonnage tax, which allowed flat-rate assessment of a ship's profitability on the basis of its carriage capacity, rather than on the basis of its actual generated revenue, made ship investments highly desirable.

At its peak, around 440,000 investors had sunk their teeth into such KGs by purchasing shares of single ship limited partnerships. This made them part owners (i.e. limited partners) of an individual vessel, so they were able to fully participate in the vessel's profits whilst their liability was limited to the value of their share, § 171 subsec. 1 German HGB (Commercial Code). At the same time, the tax treatment of the vessel was independent of the actual revenues - as discussed above, the tonnage of the vessel was the basis for a low flat-rate tax.

It goes without saying that the individuals parting with their money in exchange for tax-advantaged, zero-liability ship shares were not the most entrepreneurial sort. Rather, they were looking for high guaranteed returns with no risk.

When the going was good, financing ships on this model was no problem. The high charter rates meant that the flat-rate tax was always cheaper than the ship's actual revenue. Also, high charter rates meant that ships retained their value - in contrast to today, when certain ships are not able to be operated commercially due to charter rates not covering their costs. Today, one ship KGs have a lot more risk and a lot less return. Not surprisingly, this has led to an outflow of capital and German shipowners have had to reorient their corporate and funding models.

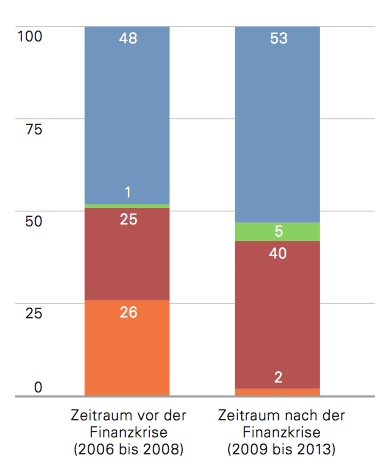

Whereas prior to the shipping crisis (around 2007), 26 percent of global (!) orderbook tonnage came from German one ship KGs. Post-crisis, that number has shrunk to a piddly two percent. In other words, the German one ship KG market has been utterly, almost completely annihilated - since 2008, over 180 one ship KGs have gone insolvent and been removed from the market.

We now see a return of more entrepreneurial and pro-risk funding actors, including private equity investors, many of whom come from the United States (e.g. Oaktree).

A popular saying in German shipping is: "Risiko ist die Bugwelle des Erfolges." In English: "Risk is the bow wave of success." With ship prices so low, it is possible to acquire even very high quality, young vessels at very reasonable prices. Like the proverbial sword hanging by a horse's hair above Damocles' head, the question remains whether even such affordable prices are able to generate sustainable levels of profit.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

As we have reported before, the supply is not adjusting downward at a sufficient pace to accommodate itself to demand; rather, ever larger newbuildings continue to arrive on the market from Korean and Chinese shipyards. Non-specialized ship management companies will therefore probably continue to suffer, at least until the number of containers finally exceeds the number of TEU available on boxships.

Are foreign investors enough to put the excitement back into the beleaguered ship finance sector? Until we find out, for countries such as Germany, it must remain a central part of the national political agenda to provide adequate financial and legal support to both ship management companies as well as dockyards so that this important industry does not leave for abroad. Having a functioning domestic merchant fleet capable of carrying German products to the world and global goods back to Germany is a vital national infrastructural asset and a major competitive advantage when it comes to locating production and distribution sites.