Fire Response Highlights Decision Complexity

One of the first things that the chief officer on the Sea Gale did when responding to an engine room fire on the 24m crew boat was to silence the fire alarm. It had served its purpose, alerting everyone on board including the master who responded immediately.

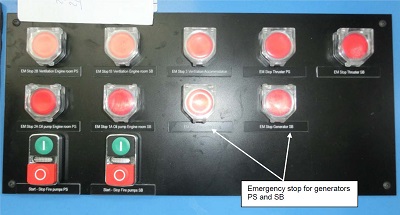

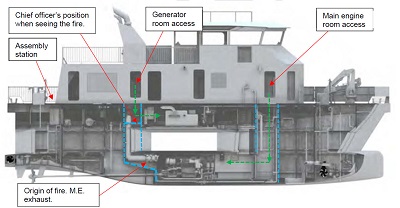

Later on during the response to the fire which occurred last year in the North Sea, he pushed the emergency stop buttons for the vessel’s engines. The chief officer subsequently activated all emergency the stop buttons, and by doing so, unintentionally also stopped the generators which caused a black-out that surprised the crew and caused an abundance of audible and visual alarms on the bridge, indicating multiple system failures. Because the noise from the alarms was causing stress amongst those on board, the master silenced as many as he could by acknowledging them on the alarm panel.

Layout Prone to Mistakes

Layout Prone to Mistakes

The power interruption stopped the water mist system after it had been activated for roughly one minute. According to the Danish Maritime Authority’s investigation, the layout and operation of the systems was such that in an emergency they were prone to mistakes. This added to what was already a complex situation, as the crew mustered the passengers, called for help and attempted to assess the engine room and deal with the fire.

The fire broke out in the transition area between the starboard main engine room and the adjacent casing. The immediate, technical cause of the fire was likely a combination of insufficient insulation and possibly elevated exhaust gas temperatures from the propulsion engine due to insufficient ventilation.

No Firefighting Outfits

No firefighter’s outfits were available, so the crew did not consider it safe to enter very far into either of the vessel’s two engine rooms to assess or fight the fire as they did not know the extent of fire or the risk of toxic smoke and fumes. This uncertainty was compounded by concern about the fire properties of the vessel’s carbon fiber construction.

In order to restart the engines after a stop, they must be reset, which could only be achieved by entering the emergency generator rooms. This would not have been an option under circumstances where the extent of the fire was unknown.

In investigating the accident, the Danish Maritime Authority highlights the complexity of the situation that the crew members had to deal with – something they did successful as they evacuated all 12 passengers safely.

Assistance Needed

The Authority also highlights though that they achieved the safe evacuation and control of the fire with help from vessels nearby. Sea Gale is classified as Category A under the IMO Code of Safety for High-Speed Craft (HSC Code) which means that it is acceptable for the vessel to need to rely on external help in such a situation.

The code was adopted by IMO in 1994 and amended in 2002. It was developed to accommodate the design and operation of vessels constructed of other materials than steel, and with a speed/displacement ratio above a fixed limit. This reasoning is based on the operational limitations of the vessels it covers, the management and reduction of risk and the reliance on outside help.

This contrasts such high speed craft from conventional ships. Normally ships and their crews should be self-assisted to some extent, and abandoning the ship should be a last resort, only to be applied if all other efforts to rescue crew, passengers and ship fail.

HSC Code vessels are not considered self-assisted and thus depend on external assistance. This was the case for Sea Gale, where the positive outcome of the events can be ascribed to the availability of assistance from other ships that supplied evacuation capacity, firefighters, equipment and pump capacity, says the Authority.

Challenges for the Crew

The crew faced a number of challenges:

• They did not have the equipment needed to effectively assess the extent and intensity of the fire in the casing,

• The layout of the controls for the firefighting and engine systems caused an unintended blackout.

• The large amount of audible and visual alarms impaired the crew members’ handling of the emergency situation.

According to the HSC Code, it is not a requirement for ships of category A to carry firefighter’s outfits with breathing apparatuses. However, in this particular situation without having repiratory protective equipment, the crew felt hindered in their efforts to move freely and safely around the ship to assess and possibly extinguish the fire before it developed.

According to the HSC Code, it is not a requirement for ships of category A to carry firefighter’s outfits with breathing apparatuses. However, in this particular situation without having repiratory protective equipment, the crew felt hindered in their efforts to move freely and safely around the ship to assess and possibly extinguish the fire before it developed.

The uncertainty about the risk of a fire in a carbon composite structure introduced further stress factors in the decision making process, thus adding to the complexity of the situation. The crew did not know to which extent the smoke and fumes from the fire were toxic, there was uncertainty about the structural strength of the ship and concern about how fast the fire might spread.

Evacuation an Immediate Response

The HSC Code requirements imply that evacuation is the immediate response to emergency scenarios. There are inherent risks in evacuating a ship where passengers are to be transferred to life rafts in open sea. This risk might make ship crews reluctant to immediately decide on evacuation before the seriousness of the situation is established, reports the Danish Maritime Authority.

It is problematic to make a decision about evacuation when it is unknown to the crew whether a situation is serious enough to abandon the ship. The extremes are usually easy to establish, e.g. a small smouldering fire in a garbage bin does usually not lead to evacuation, whereas a visible serious engine room explosion usually does.

All the situations in between may be difficult for ship crews to assess. Therefore, it is up to the crew members to assess when a situation is serious enough to abandon the ship.

Only One Option

The combination of the above factors left the crew of Sea Gale with only one option, says the Authority, to rely entirely on external assistance to extinguish the fire.

Following technical investigations, the vessel’s owner A2SEA has initiated several preventive measures including a design review of the insulation in the area of the manifolds, exhaust pipes and funnel. The changes were implemented on Sea Gale during the reconstruction. All other A2SEA operated vessels were inspected for signs of similar weaknesses.

Following technical investigations, the vessel’s owner A2SEA has initiated several preventive measures including a design review of the insulation in the area of the manifolds, exhaust pipes and funnel. The changes were implemented on Sea Gale during the reconstruction. All other A2SEA operated vessels were inspected for signs of similar weaknesses.

Further measures have also been implemented including:

• The evaluation of the layout of the emergency buttons made A2SEA remark the emergency stops on the bridge to better distinguish between them and to which redundant engine they belong. Same with the quick closing valves which have been marked more thoroughly with green and red markings.

• Checklist for main engine start up (SMS 7-0700A) have been amended where increasing of airflow prior to start up to 80 percent have been added. The duty engineer must report to the master when this is completed. A2SEA is currently working on an automatic control system where ventilation to the engine rooms is automatically initiated and closed.

• More focus on training in redundancy equipment and technical layout of the vessel in order to ensure a better familiarization with the emergency equipment on board.

The full report is available here.