Some Common Misconceptions About Arctic Shipping

Op-Ed by Dermot Loughnane, CEO of Tactical Marine Solutions, Canada

Just reading the headline of a recent article by Gary Strieker of Environment News Trust makes my teeth hurt: As Arctic Melts, Shipping Traffic Blasts Wildlife. The use of the word “blasts” gives you a hint of what’s coming, though in 35 years I’ve never seen a commercial ship blast anything.

Just reading the headline of a recent article by Gary Strieker of Environment News Trust makes my teeth hurt: As Arctic Melts, Shipping Traffic Blasts Wildlife. The use of the word “blasts” gives you a hint of what’s coming, though in 35 years I’ve never seen a commercial ship blast anything.

The article says the rush is on for shipping and oil and gas development in the Arctic. Without good regulation, it’s going to be like the Wild West. The environment and indigenous people will suffer.

Strieker is demonstrating how many people are confused and misinformed about the Arctic. The Arctic and Antarctica are quite different places (besides one being an archipelago and the other one a continent). Maybe he’s thinking of Antarctica, which is partially claimed, and it’s future is not entirely clear but there is an international treaty banning (for now) any development. The Arctic however is another matter, it is wholly claimed; in fact some parts are claimed by more than one country (hello North Pole) and subject to national regulation. Transiting the Northern Sea Route requires application to the Russian Northern Sea Route Administration for permission, which is not a foregone conclusion. In Canada ships must report through a traffic management scheme and are of course subject to the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act and the numerous regulations made under it. It may not be run the way some groups would like to see it, but the Arctic is no Wild West.

Indigenous people have demonstrated their active involvement and their power to intervene (quite rightly) in development issues that could affect them. The benefits agreement struck between Canada’s Nunavut Inuit and the Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation is one success.

It can go the other way too, local communities on Baffin Island have objected to proposed seismic exploration off the east coast of their island. In spite of an approval from the National Energy Board to commence surveying in the summer of 2015 the communities have taken the seismic company to the Federal Court of Canada to stop them. In general though, consultation on mineral and oil development is not just a notion in Canada. The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement states clearly the requirement for projects to be reviewed by the Nunavut Impact Review Board, and potentially referred to the federal government.

Strieker points the finger at shipping as well as offshore development: “Official records show that the number of tankers, cargo ships and tugs transiting through the Arctic has more than doubled since 2008.” Well, yes, but in the way that you can double your money in penny stocks and still have not much more than change in your wallet.

This is a increase oft quoted lately, but from what little I could find on this the increase was from 120 to about 250 ships, a 100 percent increase on its own, but compared to the Suez Canal (17,000 annual transits) it’s pretty trivial. Just to be clear, “transits” aren’t necessarily transits of the NWP, it’s probably more accurate to describe them as “movements” as they are destinational to and from the Arctic. At least half of the numbers cited are likely the annual resupply of the local communities from down south, and this number would include tugs and barges on the Mackenzie River, fishing vessels and government ships.

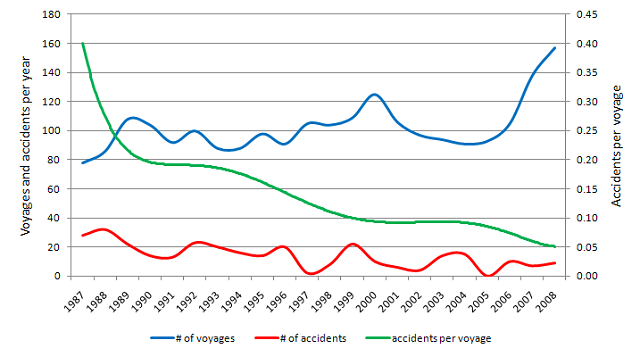

He also notes that “any industrialization there will be hazardous, raising extreme risks to life and the fragile environment”. True, except of course that the Arctic has become less risky over time. An ex-colleague of mine Brad Judson wrote a very thoughtful paper a few years ago called ‘Trends in Canadian Arctic Shipping Traffic – Myths and Rumours”, he found that: “Since 1996 the annual casualty rate per voyage is 9 percent, a considerable improvement from 1987 when the casualty rate was 40 percent.” This was in 2008 so one would imagine, absent evidence to the contrary, that rate continues to decline. A decline is not a surprise when you consider just how much more information is available to the average ship operating in the Arctic compared to 30 years ago, and, though some would find it hard to believe, better charting. (Of the recent casualties, most were government icebreakers or river tugs and barges.)

One of the major concerns raised by Strieker is that shipping and seismic surveys will have a detrimental effect on wildlife, particularly whales. The Arctic Ocean is becoming noisier, he says, quoting scientists to support his claim: “Mostly low-frequency sounds from ship engines, seismic surveys and drilling machinery overlap with and may interfere with sounds produced and received by marine animals.” This could also lead to an increased rate of collisions between ships and whales.

No argument with this except that very little seismic activity went on in the Arctic this (or last) summer, and most exploration companies have protocols for curtailing activities when high concentrations of marine mammals are likely to be present. As for collisions, we are talking about a small number of ships in a large ocean. Most collisions are going to occur in much denser traffic areas than the Arctic such as the east coast of the USA or the St Lawrence River.

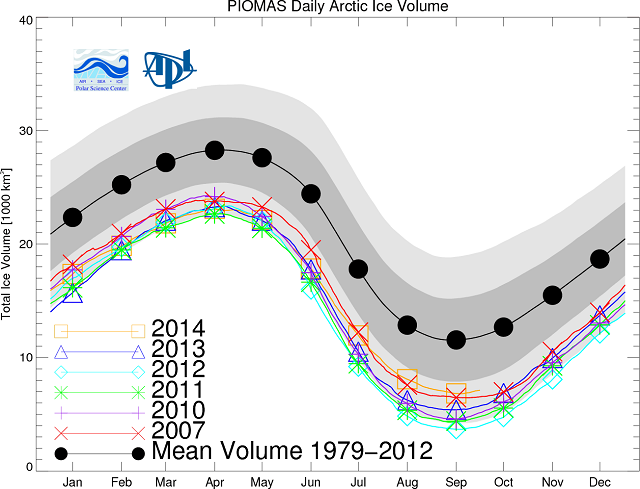

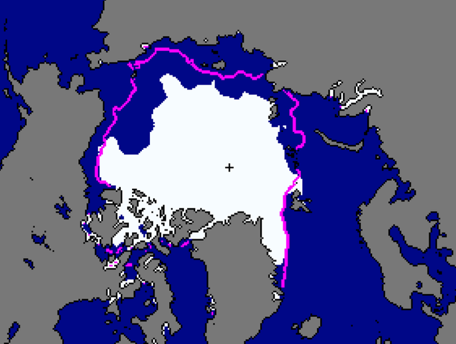

The whole basis for Strieker’s article is that the sea ice is disappearing and the route opening up. Scientists have studied the rate of Arctic melting extensively, but here again, it is easy for people to be confused. Yes, the Arctic is melting and the ice cover continues to shrink at a very alarming rate. Except of course that this year its up, way up in fact, 84 percent since 2012 according to the Polar Science Center at the University of Washington. This is not climate change denial, but it shows that global warming doesn’t necessarily mean warm weather, just weird weather, and assumptions about the opening of the Arctic are risky. That it will be open eventually is probably inevitable, but there are many years where the ice will be there in the winter and for a good portion of the summer.

Yes, there is an open water passage, but awkwardly it’s the Northern Sea Route along the northern coast of Russia that is melting first and it is here that a passage is open for a good deal of the summer. On Canada’s side of the polar cap it’s a different case entirely. Ice is melting but the period when the passage is open is still only a couple of weeks of the year, and it’s not always at the same time of the summer.

There is no doubt that the route through the Northwest Passage along Canada’s side of the Arctic is shorter for ships going between Europe and the Far East. Ships would save fuel, but fuel is not the only consideration.

The operators of container shipping companies that I have spoken with, and major operators like AP Moeller and COSCO have publicly stated, that they felt that the Northwest Passage was not going to be of interest to them for some time. Container lines function on regularity and predictability. Routing a ship through the Northwest Passage when there’s a chance of ice that could interrupt their schedule is not an option.

In addition, the draft in parts of the Northwest Passage is nowhere deep enough to allow the larger container ships in the global fleet. It is of course possible to build wider, shallower ships for the route but this adds extra expense on top of the 10-15 percent increase in newbuilding costs for ice class. Since any ship going through the Northwest Passage is going further north than the norm and therefore increasing the chance of encountering ice, (amongst other hazards), there is also an increase in insurance costs for breaking what used to be called Institute Warranty Limits.

To conclude his article, Stieker says that any solutions will need to be achieved through international agreement: “That’s a long and tedious process that needs to start now.” Without a mention, Strieker has totally discarded the work of the Arctic Council (established in 1996) and the IMO (Polar Code).