Going Global: U.S. Energy Exports

(Article originally published in Sept/Oct 2016 edition.)

The U.S. has quietly emerged as a major player in energy exports, including everything from LPG and LNG to gasoline and – yes – even crude oil.

By Jack O’Connell

It wasn’t so long ago that the U.S. was importing north of ten million barrels a day of crude oil, more than half its daily consumption, amid increased concern over growing dependence on OPEC and other foreign sources of supply. At the same time, natural gas import terminals were being constructed along the Gulf and East Coasts to make up for declining gas production at home.

Now all that has changed, thanks to the shale revolution and a little old-fashioned American ingenuity. With each passing day the U.S. becomes less and less dependent on imports for its energy needs and more and more reliant on its own resources. Starting last year, it began exporting oil for the first time in 40 years. And those natural gas import terminals? They’ve been mothballed and replaced by export facilities. By 2025, if not sooner, the nation will achieve what was once thought to be at best a pipe dream: energy independence.

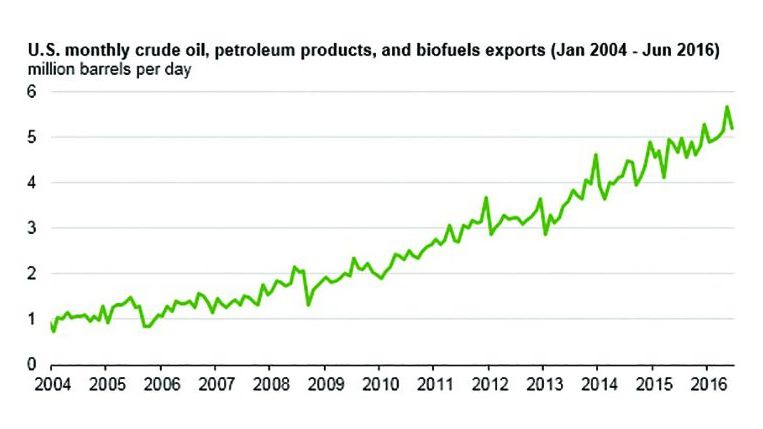

We may already be there. Oil and gas storage facilities are bursting at the seams, and prices for all forms of energy, aside from renewables, have plummeted. There’s so much oil and gas around that producers have stopped drilling in an effort to lift prices. And in the most unlikely of scenarios, the U.S. has emerged as a major exporter of energy and energy products – nearly six million barrels a day – as the accompanying chart shows.

Through the Canal

A big boost to American exports was the opening of the Expanded Panama Canal in late June. The second ship through – after the COSCO Shipping Panama – was NYK Line’s LPG tanker Lycaste Peace, carrying a cargo of propane from Houston to Hitachi, Japan. A day later Avance Gas’s LPG carrier Passat transited the locks, followed shortly thereafter by her sister ship Breeze. All three ships were VLGCs (Very Large Gas Carriers) that couldn’t fit through the old canal. These behemoths can carry upwards of half a million barrels of product, and their passage marked the beginning of a whole new trade from the U.S. Gulf Coast to Asia and the West Coast of Central and South America.

LPG, of course, is liquefied petroleum gas, not to be confused with LNG (liquefied natural gas), which we’ll get to later. It’s “wet gas,” the stuff you see flaring in oil fields, as opposed to “dry gas,” which is what heats your oven. LPG is mainly propane and, believe it or not, the U.S. is by far the world’s leading exporter – nearly a million barrels a day. About half of it goes to Latin America and the rest to Europe and Asia.

But Asia is the big potential market, and now the U.S. can reach it because the Expanded Canal cuts two weeks and nearly 7,000 miles off the voyage from processing facilities along the Gulf Coast to Asian destinations, reducing shipping costs and making U.S. LPG competitive with Middle East production. And the fact that freight rates for LPG carriers are currently at rock bottom doesn’t hurt either.

LPG, in the form of ethane, propylene and ethylene, can also be used as a petrochemical feedstock for the production of plastics, and this has huge potential application in countries like China, which is ramping up its petrochemical production and currently depends on more expensive naphtha, which is oil-based, for most of its feedstock requirements. Exports of U.S. ethane and ethylene have been growing rapidly with Asia the main market.

As for LNG, it’s got a long way to go before it catches up with LPG, but a start was made with the passage of Shell Oil’s Maran Gas Apollonia through the Expanded Canal in late July. It was carrying the first shipment of LNG to transit the canal from Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass terminal in Louisiana. It was followed the next day by BP’s British Merchant, carrying LNG from Trinidad & Tobago. Both cargoes were headed for Mexico.

The Expanded Canal can handle 90 percent of global LNG carriers, up from 30 percent previously. Citigroup analyst Ed Morse, among others, sees the U.S. Gulf becoming a major LNG trading hub in the next five years, right up there with the Middle East and Australia. As more LNG “trains,” as they are called, come online at Sabine Pass and elsewhere along the Gulf Coast, U.S. output will increase to more than 40 million tons annually over the next three years, Morse adds, equivalent to roughly 20 percent of the current global trade in LNG. That’s a big piece of the action.

Right now the U.S. has only one LNG train in operation – Sabine Pass #1, which began exporting product in February. Sabine Pass #2 is scheduled for startup later this year, with four more trains to follow over the next three years. Each train can produce 4.5 million tons a year. At an average conversion rate of one ton of LNG = 10 barrels of oil equivalent, that’s 45 million barrels a year or 125,000 barrels a day. If Morse’s projections are right, the U.S. will be exporting well over a million barrels a day of LNG come 2019.

On the demand side of the equation, there’s no shortage of buyers. Japan, South Korea and China are the three biggest, accounting for more than half of all global LNG imports. Taiwan and India are next. All of these markets are now readily accessible to U.S. LNG thanks to the Expanded Canal, and let’s not forget about our neighbors to the south, particularly Mexico and Chile. They are huge importers of LNG.

The environmental implications of all this are also important. Not only is gas cleaner burning than the coal and oil it is replacing, but the fact that the transit time to destinations in South America and Asia is cut roughly in half means reduced emissions from the ships themselves. The Panama Canal Authority is well aware of this and bestowed its Green Connection Award on the Maran Gas Apollonia for contributing to the “protection and conservation of the environment” by using the canal.

And in an ironic footnote to the LNG demand story, my colleague Allen Brooks points out that the Middle East, of all places, has emerged as a surprise importer of U.S. LNG. At least two cargoes in recent weeks have been delivered – one to Kuwait and one to Dubai. Who’d ?a thought? I thought the Middle East was the world’s leading producer of LNG, not to mention crude oil and everything else related to energy. Well, it is, but the demand for energy there is growing so fast, says Brooks, and particularly in the hot summer months, that some OPEC members have turned to the U.S. for relief. Wonders never cease.

Crude & Crude Products

Here’s the next wonder: The U.S. is becoming an important crude exporter. That’s right – exporter. More than half a million barrels a day and growing. Most of it goes to our neighbor to the north, but increasing amounts are finding their way to Europe, where “sweet” oil (i.e., low sulfur content, like U.S. shale oil) is in high demand.

Refined products like diesel and gasoline are an even bigger U.S. export. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the U.S. exported nearly four million barrels a day of finished petroleum products, fuel ethanol and natural gas liquids in August – an amazing number – and nearly six million barrels of energy exports of all kinds, an even more amazing number.

Why is all this important? Because it provides a much-needed outlet for burgeoning U.S. supplies and helps relieve downward pricing pressures. It also helps offset imports of oil and related products and improves the nation’s balance of trade. And on the geopolitical front, it sends a message that the U.S. can no longer be held hostage to energy embargoes of any kind.

In fact, the U.S. may soon be the “swing” producer when it comes to energy. U.S. LNG could help relieve Russia’s chokehold on European gas supplies. U.S. gasoline and diesel can bolster Latin American markets and make up for shortfalls in other parts of the world. In times of political turmoil in the Middle East and elsewhere, the U.S. can act as a stabilizing force in energy markets and now has the resources to do it.

How to Play It

The obvious choice on the LNG side is Cheniere Energy, whose ticker symbol, not surprisingly, is LNG. Right now it’s the only game in town. But there will soon be others, and Cheniere is a debt-laden company whose stock peaked a year and a half ago and which is still struggling to prove itself. With one LNG train up and running, it needs to successfully complete its other five trains at Sabine Pass and three at Corpus Christi to generate meaningful cash flow and begin paying down debt.

Better bets are companies on the LPG and midstream side of the petroleum business like Energy Transfer Partners (NYSE: ETP), Enterprise Products Partners (NYSE: EPD), Targa Resources (NYSE: TRGP) and Phillips 66 (NYSE: PSX). While down from their recent highs, all of these companies pay very attractive dividends and will benefit from any increase in oil and gas prices.

Did I mention shipping companies? ?Fraid not. With freight rates in the doldrums, including those for LNG and especially LPG carriers, why bother? The risks are too great. The only maritime companies worth investing in these days are non-shippers and cruise operators. Otherwise, take a pass. – MarEx

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.