Repeated Collisions Led to Maersk PSV Sinkings

The Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board has released its report into the sinking of the decommissioned PSVs Maersk Searcher and Maersk Shipper in December 2016. The DMAIB concluded that the fenders between the two ships failed during a side-by-side tow through the English Channel, and that the ships collided repeatedly until damage and flooding caused them to founder.

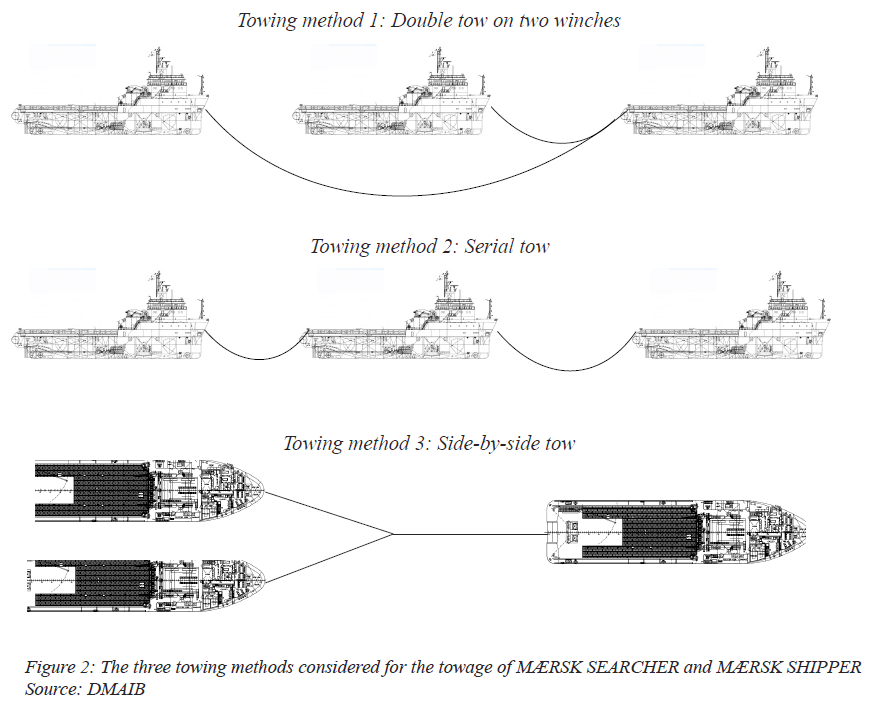

The two aging Maersk Supply ships were prepared for scrapping in 2016. In the summer, a Maersk superintendent began drafting plans for towing them to the scrapyard using an AHTS, the Maersk Chancellor, and began to draft plans for the evolution. The Chancellor lacked the winch arrangements for a standard double tow, so the superintendent began to plan for a side-by-side tow on one wire – not a standard arrangement for ocean towing.

However, the superintendent was laid off in a round of dismissals before the tow got under way, and he was not given time to hand off his work to his colleagues. Shortly thereafter, another round of reorganization completely replaced the leadership for Maersk Supply's Europe operations.

A trainee took over the preparations for the tow in December under guidance of the new operations manager. The team assumed that the draft plan for the towing rig was finalized and approved, and that all was ready to go. However, the initial draft was not a finalized towing plan, and it was not designed for the towing vessel that Maersk Supply decided to deploy – the Maersk Battler, not the Chancellor. The Battler was equipped for a double tow and did not need the special side-by-side arrangement developed earlier.

With the Searcher and Shipper rigged side-by-side, the Battler left Fredericia on the morning of December 12. After taking on stores she headed south through the North Sea in fine weather. On December 20, as she was transiting the English Channel, the swell increased and the crew paid out the tow wire to about 2,000 feet. At this time, they noticed that the fenders between the two PSVs had disappeared, and that the vessels' hulls were making contact (below).

The crew did not believe that this posed a problem, as the vessels were due to be scrapped anyways, and the captain planned to inspect the ships further upon reaching the Mediterranean. Inspecting them in choppy conditions in the Channel or the Bay of Biscay was considered too hazardous.

The weather worsened on December 21, with westerly swells reaching 15 feet. In the morning, it was clear that both vessels had suffered damage to their superstructures, and that they were listing towards each other (below). Again, the crew did not perceive that this posed any serious risk, as the damage appeared to be above the waterline. The vessels continued to collide into the night.

At about 2330, the watch AB observed that the Searcher was riding deeper in the water and listing heavily. He alerted the master, who realized that Searcher was about to capsize. She went over about ten minutes later, and threatened to drag Maersk Shipper down with her by the bridle. The tow wire was at about 800 feet, much more than the water depth, so Maersk Battler was in no danger from the sinking.

Searcher went down at 0022, and Shipper capsized a few minutes later. The second vessel stayed afloat until 0600, when she followed her sister ship to the bottom.

In an after-accident analysis, DMAIB concluded that:

- the fendering was not sufficient to withstand the force of the repeated impact of the two vessels.

- the crew failed to recognize the developing emergency, in part because they assumed that the damage was acceptable for the decommissioned vessels.

- the impact damage penetrated the vessels’ watertight envelopes, leading to progressive flooding and capsize.

- the towing arrangement and towing plan made no provisions for disconnecting the two vessels in an emergency, raising the risks from a casualty involving one ship.

More broadly, DMAIB noted that Maersk Supply had used industry-standard tools to evaluate the risks associated with the voyage and had moved ahead anyways – pointing to the limitations of the risk management system itself:

“The risk management system offers to handle risk as an objective value and to provide a structure for handling risk. However, there is no aid or control of what is put into the system . . .The numeric risk value is based solely on how imaginative the involved persons are,” DMAIB wrote. “The assessment of the risk reduction is highly sensitive to one or more individuals’ subjective risk perception, which will be strongly influenced by the desire to make the operation possible. Thereby, the risk management system will rarely limit activities prone to risk. In fact, the risk management system instead tends to facilitate the carrying out of risk prone operations.”