Near Miss Reporting Lacking in the U.S.

Let’s talk about near miss reporting. If there is a subject sure to get eyes rolling and profanities muttered under people’s breath in the maritime industry, it’s the topic of near misses and their reporting.

Near misses, near miss reporting systems and accident investigations are of great interest to me and, in my humble opinion, should be of great interest to mariners as a group. As the readers start rolling their eyes and muttering under their breath, the prevailing thought is likely, “Why?” The answer is something I say quite often, “I’d much rather learn from someone else’s mistakes or near misses than make them myself.”

Then again, as colleague of mine will often say, “Sometimes you have to realize that your purpose in life is to be a cautionary tale for others.” It’s up to you to decide which path you might follow.

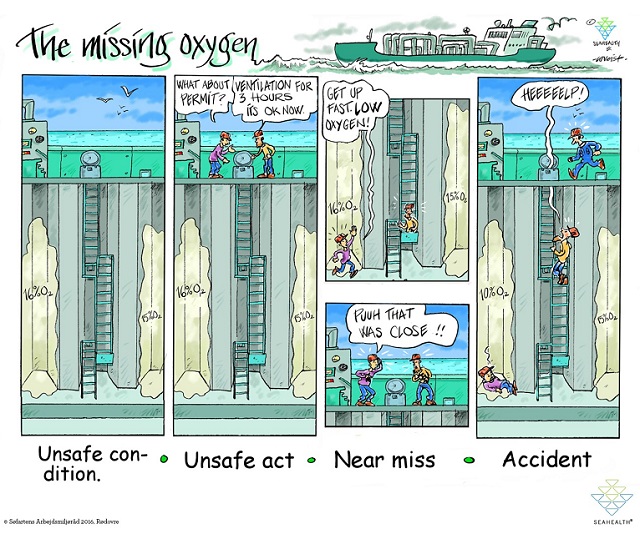

Credit: NearMiss.dk

The Theory

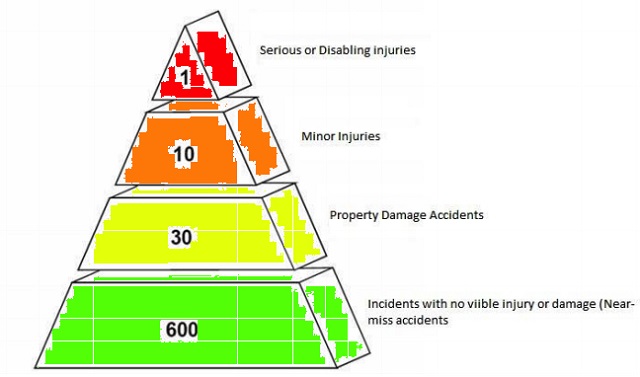

The theoretical advantage to near miss reporting is pretty clear. Whether you are referring to Heinrich, Petersen & Roos (1980) or Bird and Loftus (1976), the correlation of around 600 near miss accidents to a single serious or fatal accident might encourage us to look for some of those near misses. Those near misses, unsafe conditions or unsafe practices, if identified, are leading indicators that some type of incident or accident might occur if left unchecked. Frequently, the error chain or causal chain that would bring about that incident is broken before it occurs. It is in these instances that the identification, investigation and dissemination of near misses may help others in a company, organization or industry avoid their own similar near misses or incidents.

Regardless of whether or not the exact ratios of Heinrich, Petersen, Roos, Bird and Loftus are correct (and there are a number of scholarly articles purporting to debunk Heinrich), the effectiveness of near miss reporting as a leading indicator of safety remains. Stopping the error chain at the unsafe condition, unsafe act or near miss is far preferable to dealing with an accident, the ensuing investigation and report that may be detrimental to the individual or organization.

Studies of near miss reporting are almost universally in agreement that the reporting, analysis of causal factors and dissemination of near miss data can help prevent accidents from occurring. Under the International Safety Management (ISM) Code from the IMO, shipping companies should encourage the reporting of near misses to maintain and improve safety awareness. Therefore, near miss reporting on a company or organization level within the maritime industry is widespread. But, is this helping the maritime industry as a whole?

Maritime Near Miss Reporting Schemes – International

Near miss reporting schemes for the maritime industry are relatively widespread on the international level. Not only do you have the company or organization-level schemes mandated by the ISM Code, but there are a variety of national and international schemes available.

On the national level, NearMiss.dk is a joint cooperation between the Danish Shipowners’ Association and SEAHEALTH. It is set up both as a common database to which shipping companies contribute and such that companies can manage their company near miss reporting, including corrective actions, preventive measures and follow up, separately.

Foresea.org, a collaboration between Sweden and Finland, is based on the Swedish Insjo.org, which is now defunct. With over 3,000 reports (as of 2014) in English, this is a good resource for the industry as a whole.

On the international level, there are two near miss reporting schemes to discuss. The first is run by The Nautical Institute, an international representative body for maritime professionals involved in the control of sea-going ships. The Mariners’ Alerting and Reporting Scheme (MARS) has been accepting reports since 1992 and has a significant database built up. As many near miss reports as possible are published in their monthly Seaways magazine.

The second international scheme to discuss is the U.K.’s Confidential Hazardous Incident Reporting Scheme (CHIRP). Building from the successful implementation of CHIRP in the aviation industry, it’s scope was widened to the maritime industry in 2003. Designed to be complementary to other government and organizational reporting systems, this scheme has become known internationally and accepts near miss submissions from all.

CHIRP is run as a charitable trust, thus maintaining autonomy from other industry organizations. The reports are de-identified and then passed along to organizations that can follow up on them. Frequently this will include dialogue with the reporter to gather additional information. Additionally, other parties to the near miss will be contacted to obtain their point of view, as well as to alert them to the near miss. At all times, great effort is taken by CHIRP to avoid identifying the reporter.

CHIRP publishes their findings and near miss reports on a quarterly basis in their Feedback magazine. They have also started to produce videos highlighting many of their near miss reports, as well as identifying some industry best practices.

Having had the opportunity to report near misses to both The Nautical Institute MARS and CHIRP, I found the submission of the reports quite easy over email. The follow up by both organizations was excellent, with CHIRP contacting the third party for comment and attempted resolution of unsafe work practices.

While the third party in my report did not respond to CHIRP with comment (continued communication with CHIRP allowed this feedback to the reporter), the unsafe work practice appeared to have been mitigated in future interactions. In both cases, the near miss reports were published by MARS and CHIRP, allowing other mariners to learn from my near miss.

Near Miss Reporting in Other Industries

The maritime industry is certainly not the only high-risk, high-consequence industry. High Reliability Organizations (HRO) are those that have succeeded in avoiding catastrophes in environments where normal accidents can be expected due to risk factors and complexity. Aviation, nuclear power, health care and military operations such as aircraft carrier operations are examples of these HRO. Although these organizations routinely avoid serious incidents, they are not without them; and occasionally, they are catastrophic. One of the characteristics that define these HRO, though, is that they continually strive to learn from these incidents, as well as near-incidents or near-misses. In fact, they actively seek near miss reporting so as to head off bad things before they happen.

The Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) has enjoyed success to a large part due to its use of the National Aeronautics and Space Agency’s (NASA) Ames Research Center as an independent third party. As a third party organization, NASA is outside the regulatory, administrative or enforcement processes of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). NASA collects, analyzes and collates the near miss reports. This safety information is then disseminated to the aviation industry.

Since 2010, these processes have been conducted under contract by Booz Allen Hamilton of Sunnydale, California. Over the course of its 42-year history, the ASRS has collected over 1.3 million near miss reports, issued over 6,200 safety alerts, authored or supported 60 research products and continues to put out a monthly safety newsletter that is distributed to over 30,000 subscribers.

The U.S. aviation industry embraced the ASRS based on the tenets of being confidential, voluntary and non-punitive. It is confidential, not anonymous. This allows investigators to follow up with the reporter to gain more information and verify the veracity of the report. Being voluntary, making an ASRS report is not mandatory. It is widely recognized within the aviation community, however, that reporting a near miss allows one to self-identify a fault in a system or process so that others may learn from it. Lastly, being non-punitive, the FAA under federal regulation may not use a report to the ASRS for enforcement action unless it concerns an accident or criminal offense.

NASA has gone on to act as the third-party organization for the U.S. medical and railroad industries near miss reporting schemes. The Confidential Close Call Reporting System (C3RS) for the railroad industry and Patient Safety Reporting System (PSRS) for the medical industry are both based on the system in place for the ASRS. They, too, are currently administered under contract by Booz Allen Hamilton.

Other near miss reporting schemes within the U.S. exist for firefighters and the oil and gas industry operating on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS). The near miss scheme for firefighters is administered by the International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) and, although relatively young (launched in 2005) has a robust following of 9,000 subscribers for their weekly report.

SafeOCS for the oil and gas industry was developed jointly by two government agencies. These were the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) and the Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS). In place since 2013 for the collection of near miss information, SafeOCS now collects required reports on equipment malfunctions, as well.

Maritime Near Miss Reporting Schemes – U.S.

Predating the introduction of the ISM Code, the U.S. National Research Council in their 1994 publication, Minding the Helm, discussed the fact that the underlying causes of maritime accidents were not being addressed. Additionally, it noted that the marine safety data available at the time was not adequate to identify the causal factors and any preventative measures that could be applied. Sounds like a system of near miss reporting could be of use…

By 1998, when much of the shipping industry was required to be in compliance with the ISM Code, the U.S. attempted to develop a near miss reporting system of their own. Called the International Maritime Information Safety System (IMISS), it was created when a memorandum of agreement was signed between the U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) and the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG). It was intended that the system would allow both agencies to receive, analyze and disseminate information about unsafe occurrences.

Development of IMISS moved forward, with NASA’s ASRS working with the USCG to develop the reporting form. This prototype form was then used by 87 mariners to report a simulated incident. Analysts, including human factors and maritime representatives, then reviewed the submissions and assessed how completely the incident had been described.

Despite receiving widespread support from the maritime industry, shipping companies and regulatory agencies, IMISS stumbled on one of the three tenets that had helped ensure the success of the ASRS. Those three tenets were that the reports were confidential, voluntary and non-punitive. While the confidentiality was problematic in the maritime industry, as there are fewer mariners working in a geographic area, thus allowing deduction of a reporter’s identity, it was the non-punitive nature on which IMISS eventually failed.

Unlike the ASRS where statute ensures that reports will not be used in enforcement action, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) had a different view of the maritime industry. “The DOJ found it unreasonable to provide protection from civil fines and certificate action for inadvertent incidents.” Due to these objections, IMISS stalled and the USCG withdrew funding. Industry and Department of Defense(DOD) support remained strong, but there failed to be a way forward for the program.

2012 rolled around and the Ship Operations Cooperative Program (SOCP), a non-profit organization of commercial ship operators and maritime stakeholders in the U.S., commissioned a study for MARAD to the determine the needs for a centralized marine safety data network. Ironically, the author of this report was Mr. Alexander C. Landsburg, a former MARAD representative to IMISS.

The SOCP/Landsburg study was comprehensive, covering all aspects of near miss reporting from the theory, to potential sources of maritime operational safety data and barriers to effective implementation of a near miss reporting scheme. Various conclusions were drawn from this in-depth analysis, including the value of such a network. Certainly, shipowners would benefit due to their financial and reputation risk in the event of incident. Government agencies would benefit as well – specifically, USCG being responsible for regulation of the recreation and commercial maritime industries, USCG and NTSB in investigating maritime accidents and, lastly, the U.S. Navy with concerns about the safety of their vessels. That last benefactor, the U.S. Navy, would revisit their vessels’ safety issues in unhappy circumstances just five years later.

The outcome of this study in 2012 was an influx of funding from SOCP and MARAD for the American Bureau of Shipping’s (ABS) Maritime Safety Research Initiative (MSRI) and Mariner Personal Safety (MPS) project. The MSRI/MPS is a collaborative program between ABS and Lamar University to develop a large international database and online repository of maritime injury and close call (near miss) reports. Their website currently claims over 100,000 reports from 31 data sources. A variety of best practices and reports have been published by the MSRI, but do not appear to have been updated past 2016.

In 2016, the U.S. Coast Guard’s Navigation Safety Advisory Council (NAVSAC) was tasked with discussing and developing a near miss reporting program that includes criteria for reporting and cataloging near miss data. Specifically, the requirements for reporting navigational near misses – collisions, allisions and groundings – were to be discussed. It’s interesting, in retrospect, that the previously attempted program, IMISS, might have been fulfilling the needs of the USCG for close to 15 years by this point, had it not been defunded.

The U.S. Navy, five years after it was noted by SOCP/Landsburg that they (the U.S. Navy) could benefit from a near miss reporting system, experienced two fatal collisions in June and August of 2017. In total, 17 U.S. Navy sailors lost their lives. These incidents, along with others, sparked a “Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents,” which was published in October 2017.

Once again causal factors and near miss events are referenced. How many near collisions had the U.S. Navy experienced since IMISS was defunded? Might they have identified some causal factors or best practices that could have avoided the eventual loss of life?

Barriers to Near Miss Reporting

In the early 2000s when IMISS was defunded, communication obstacles to reporting from remote areas of the world was considered an impediment to implementation. In the years since, with the introduction of internet access to most crew on vessels, reporting via email or web form is easily done. Like everything else, there could simply be “an app for that.”

Technology is no longer the issue. The biggest barrier to near miss reporting remains that elusive element that we are partially trying to address with near miss reporting; namely, that which makes us human – the human element.

The fact remains that the real obstacles to near miss reporting are built into the human psyche. Raising issues with a company or organization’s processes, personnel or equipment potentially risks one’s livelihood, promotions and reputation. These risks, on a personal level, are not insignificant as they threaten the ability to put food on the table and a roof over the head.

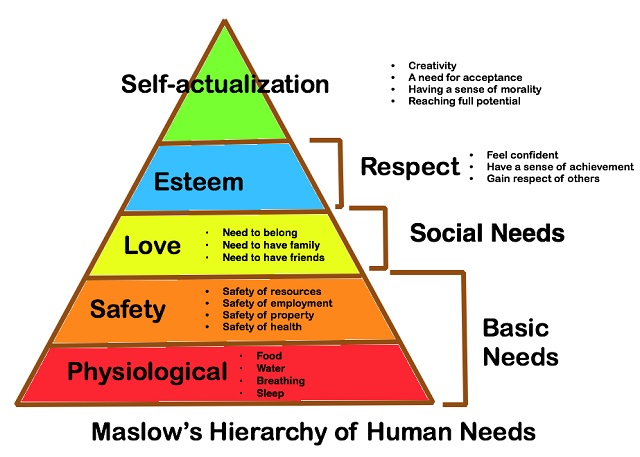

Abraham Maslow, in his Hierarchy of Human Needs (1943), opined that for one to move to a higher level on the pyramid, the needs on the lower levels must be satisfied.

If we threaten the basic needs of food, water and shelter by threatening one’s employment when safety issues are brought forward, the requirement to work safely (safety of health) may not be as important. Therefore, a person who is threatened with the loss of their job may be more apt to work unsafely. A blame culture can play no part in a near miss reporting system. Placing blame or taking disciplinary action based on near miss reporting will only suppress participation.

Ironically, there is an area where Maslow’s hierarchy fails when addressing the priority placed on safety. That point involves peers and social needs. It is not uncommon for people to disregard wearing of personal protective equipment or stringently following safety protocols if they feel doing so will harm their social position. This aspect of human psyche is quite perilous, as it places the safety of resources, employment, property and health at risk simply to belong and maintain standing in a social group.

Esteem or reputation is yet another area where we risk losing the prospective near miss reporter. Reporting minor near miss events is not normally a concern to the reporter. Whether it be an unsafe act or unsafe condition, it does not necessarily reflect poorly on the reporter. It is the near miss that we have all likely experienced on vessels, where, as the surge of adrenaline recedes and we start thinking more clearly, realize just how close we came to an accident or incident. In hindsight, we also realize what we should have done or what might have been differently. Revealing this to our peers (or company management) may damage our perceived reputation and be an impediment to reporting.

The tenets of the ASRS effectively mitigate many of the barriers to near miss reporting. Being confidential, non-punitive and voluntary, the potential negative effects on the human psyche are minimized. In discussion, many push for anonymous near miss reporting that on the surface appears promising. Unfortunately, the ability to follow up and gather additional information or provide feedback to the reporter is lost. Additionally, anonymous reporting opens the door for vindictive, misleading or false near miss reports. With strict confidentiality, one might have the best of both worlds – retaining the ability for communication with the reporter while minimizing abuse of the system.

The non-punitive aspect of ASRS would be critical in addressing and implementing the same in the maritime industry. Understanding that near miss reporting doesn’t replace incident reporting or cover up criminal or negligent behavior, the use of near miss reports in personnel evaluations or disciplinary actions cannot be allowed. The goal would be to avoid a “blame culture” while retaining personal accountability and striving for improvement in safety.

The Way Forward

The existence of the ASRS in the U.S. provides us with a solid model on which to base the Maritime Safety Reporting System (MSRS). That IMISS was so close to being established as a near miss reporting system shows that there is a need and a will to have one. The question is, where do we go from here?

The issue that caused IMISS to fail was the possibility of using near miss reports in enforcement action. The ideal would be to have the Department of Justice recognize the value of a maritime near miss reporting system and mirror the stance taken with ASRS; namely, that reports not be used for enforcement action unless they involved an actual incident or criminal offense.

Second to that, regulation could be pursued through Congress to add the MSRS to the CFR, much like the earlier excerpt for the ASRS. Failing both of those, there appears to be enough support within commercial entities and government organizations for the MSRS to move ahead, even given the risk of use in enforcement actions. The biggest question in that third scenario - the one where the non-punitive nature is not guaranteed - would be the negative effect on reporting.

In terms of who the non-partial third party should be for collection, analysis and dissemination of the near miss reports, NASA would be the obvious choice. The day to day workings of the program would likely be undertaken by Booz Allen Hamilton, as their contract already exists for ASRS. The same contract allows for expansion and growth into other fields.

Barring NASA’s participation in the MSRS, the non-partial third party’s role could be played by a newly developed trust. Such a trust could be modeled on the U.K.’s CHIRP with funding through government grants and industry organizations, such as P&I clubs. The biggest drawback to utilizing a trust would likely be the slow growth and acceptance within the maritime industry of such a scheme.

Through the ABS and Lamar University partnership of MSRI/MSP, we have seen an attempt to create a near miss reporting scheme using a classification society to collect, analyze and disseminate reports. The use of such an organization skirts the line of having a body with regulatory powers involved with the collection of near miss reports. The impartiality of classification societies has been debated in many notable maritime incidents. Ranging from the sinking of Marine Electric to Leros Strength to El Faro, questions have arisen as to whom the classification societies are beholden being that their source of revenue are shipowners.

Additionally, as classification societies can be designated recognized organizations (RO) for the purposes of statutory surveys and classification work by flag states, including the U.S., they are very close to being regulatory agencies.

Moving forward, there is a need for an increased focus on safety. This has been recognized by industry organizations ranging from the U.S. Coast Guard to the U.S. Navy to MARAD to SOCP to shipping companies themselves. One method of bettering the overall safety culture and reducing incidents is to create a comprehensive near miss reporting system that draws from the experiences of all. The only question that remains is, “When do we start?”

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.