Accident Simulation Beats Faulty Memories

Often legal cases arising from accidents at sea go to court a long time after they occur, and often the memories of those involved are imperfect and selective, even just after an event. This makes it difficult to determine the sequence of events leading up to a collision or grounding.

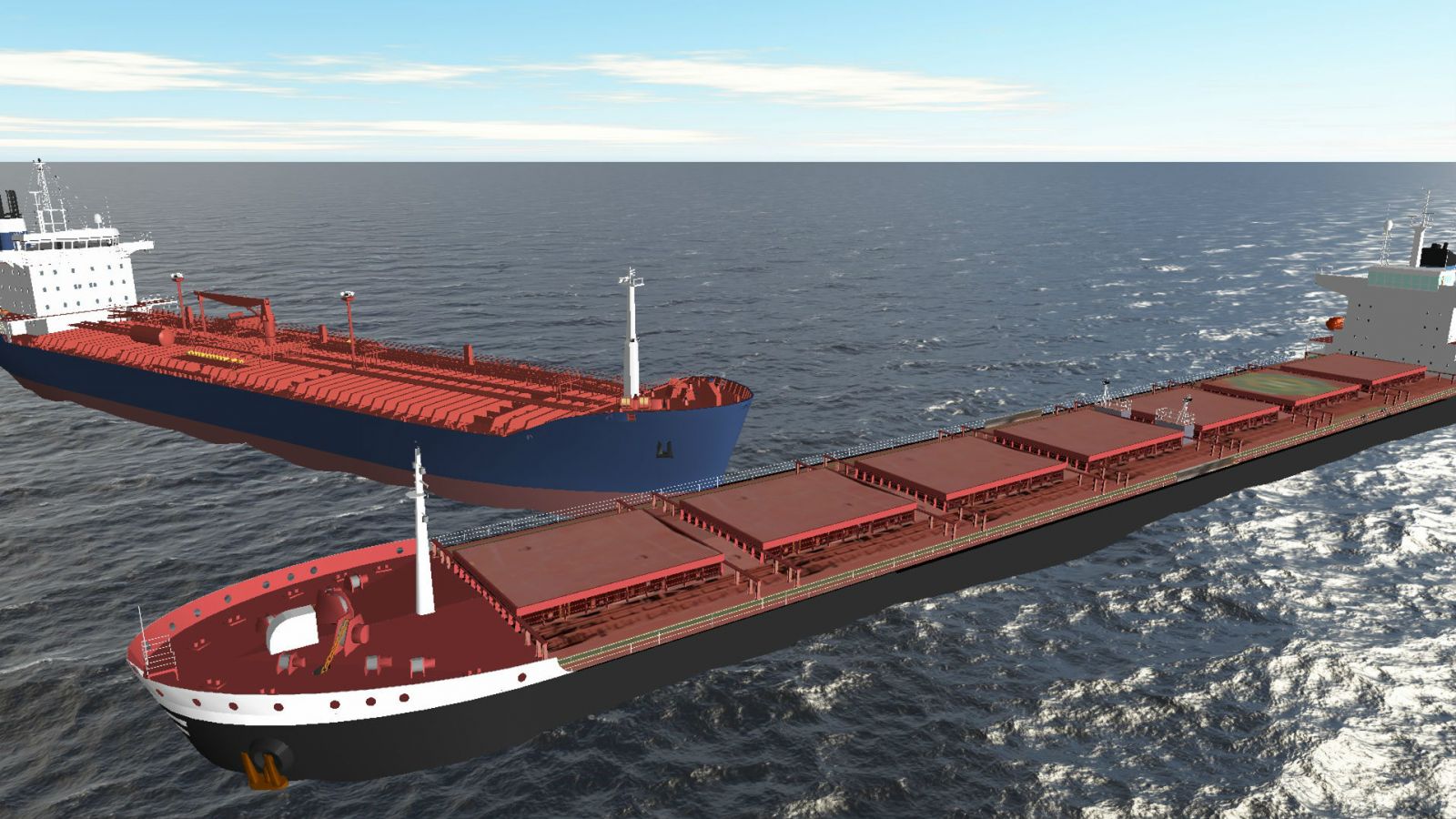

BMT ARGOSS launched BMT’s Collision Reconstruction & Simulation Team in October 2014 to help determine the causes of accidents. They have undertaken assignments on behalf of vessel owners and charterers, P&I Clubs and hull and machinery underwriters and law firms.

BMT ARGOSS reconstructs the event on the basis of the VDR / AIS data in either a 2D or 3D, with or without the audio recordings, says Paul Morter, Business Line Manager at BMT ARGOSS, a subsidiary of BMT Group. All other available data, including logbook and officers’ statements, is subsequently cross-referenced with these reconstructions in order to verify its reliability.

“In a number of the cases we have handled, we were appointed a considerable time period after the event occurred, in some cases even years later when the matter went to court,” says Morter. “Initial investigations have then been carried out by local surveyors, and we have to rely on their expertise and nautical insight to derive the human factor involved in the event.

“We have come across cases where officers were interviewed by local surveyors and, when cross-referencing these statements with the reconstructions, we ascertained that the statements were incorrect, as the reconstruction clearly showed other chains of events, or that the verbal statements on the VDR audio recordings made on the bridge contradicted the written statements drawn up at a later stage.

“The human mind remembers selectively and memories are always subjective. We have handled cases where the officers involved were absolutely convinced about certain events, whereas the VDR data clearly showed the opposite.”

In collisions, the liability almost never lies entirely with only one vessel. Under the Colregs, in particular under Rule 2, all vessels are required to act in order to avoid immediate danger.

“We have handled a matter where a large vessel collided with a small fishing vessel. Due to the presence of abundant background lighting on her portside, the navigational watch on the vessel for which we carried out the investigation, did not note the small vessel until a close quarters situation existed. The smaller, give-way, vessel had maintained her course and speed, had not contacted the large vessel and finally collided with the port bow of the large vessel, despite the evasive maneuver carried out by the large vessel at the last moment.

“The investigation revealed that the skipper of the small vessel had stated that he had seen the large vessel on his starboard side but had considered that the large vessel would pass ahead of her. As a result, he had not continued to monitor the progress of the large vessel until the horn on the large vessel was sounded less than a minute before the collision. Even though he could have altered course at that stage to avoid the imminent collision - the small vessel had a small turning circle - the skipper lost valuable time in assessing the situation and deciding on an evasive maneuver before undertaking action.”

In another case, a give-way vessel decided to alter course to starboard for the stand-on vessel coming from its starboard side when it was almost dead ahead of the stand-on vessel at a distance of approximately three cables and well within its turning circle. Why the officer on duty of this vessel decided, at such a late stage, to alter course towards the stand-on vessel, could not be verified and an assumption had to be made on the basis of the VHF recordings that were available.

“The use of simulations showed that there was very little that the stand-on vessel could have done to avoid the collision once the give-way vessel suddenly decided to alter course towards her. Given the fact that she was the stand-on vessel, she initially maintained her course and speed. However, the bow crossing distance of the give-way vessel should have been monitored more closely and speed could have been reduced at a very early stage, when the vessels were still several nautical miles apart, in order to increase the bow crossing distance and thus avoid the close quarters situation and subsequent collision.”

Therefore, says Morter, as well as accident investigation, simulations can be used to train officers in situations that have actually occurred and show them the result of certain (non-) actions and the dangers of other actions.

The products and services herein described in this press release are not endorsed by The Maritime Executive.